The second part of our urban trip (read the first one here) along the Aurelian Walls of Rome begins at St. John Lateran, one of the city’s four major Basilica (the highest-ranking Catholic churches) and the official cathedral of the capital. Consecrated in 324, its baroque architecture mostly dates back to the 17th century and is the work of Francesco Borromini. Besides the Basilica, the Lateran complex consists of other palaces and sanctuaries, including the one with the Holy Stairs which, according to Catholic tradition, was used by Jesus to go to his trial. During the second half of the twentieth century the large square in front of the Basilica, Piazza San Giovanni, became a favourite location for political demonstrations and it hosts the annual International Workers’ Day worker’s day concert on the 1st of May, organised by the national labour unions.

Here you will find both the Roman gate (Porta Asinaria) and the Papal one (Porta San Giovanni). The latter consists of a single arch opened in 1574, and it seems a more appropriate entrance to an elegant villa than a defensive structure. This is especially evident if you compare it with its Roman neighbour, Porta Asinaria, which stands a few meters lower on the “ancient” ground: it is a typical gate of the original Roman design, with two protruding, horseshoe-shaped towers and a relatively small arch at the bottom. You will see this layout often in the southern gates of the Aurelian Walls, as their ancient architecture is better preserved than their northern counterparts, and their calmer surroundings make them easier to enjoy.

After Porta Metronia the atmosphere changes suddenly as you leave behind the mad traffic of the centre and enter a quiet residential area where the walls form the background to a park.

Between Porta Latina and Porta San Sebastiano (both of whom are quite well preserved per the original design) lies the Park of the Scipios. The green area is a good place to enjoy a relaxed afternoon, but it nevertheless throws you back in time to the Roman era. Hidden in the trees you find the Columbarium of Pomponius Hylas, an exceptionally well-preserved building built to house cinerary urns from the 1st century CE. If you are familiar with Roman history, you might wonder what the park has to do with the Scipios: here you will not find the graves of the legendary leaders who defeated Hannibal and Carthage, but rather this is the common tomb of their patrician family, and one of the most prominent dating from the Republican era.

The tomb, like others that protect the remains of important people, is located along the ancient Via Appia, called by the Romans Regina Viarum, or “Queen of the roads”, so-named because it linked Rome with Capua, Naples, Taranto and Brindisi, and because of its strategic and commercial role it was considered the most important road in the Roman road system. It was a sort of gate to the Mediterranean.

A modern Via Appia still exists today and follows more or less the original route, but it starts at Porta San Giovanni, while the original Appia, named Appia Antica, is not wide enough for heavy traffic and forms part of a large archaeologic park popular among citizens and tourists alike.

The gate of such an iconic road should reflect its importance, and for this reason Porta San Sebastiano (Roman name Porta Appia) is the largest of the Aurelian Walls. The area surrounding it is sparsely built and the towering twin blocks of the gate still dominate the landscape, giving a good idea of the impression that travellers of the epoch got arriving from the south. When the Mediterranean was the centre of the world, this was surely the most important access route to Rome. To remind the visitors of today of this, the municipality put the Museum of the Aurelian Walls, where you can learn the detailed history of the monument (complete with a visit to the upper guard walk) inside Porta San Sebastiano. Behind the gate is the Arch of Drusus, a fornix of the aqueduct Aqua Antoniniana, and a branch of the great Aqua Marcia that served the Baths of Caracalla.

Following the walls and its imposing towers, you reach Porta Ardeatina – a small gate hidden in brush and therefore difficult to approach. From here begins Via Cristoforo Colombo, the longest and largest urban avenue in Italy, which links Rome with its coastal neighbourhood of Ostia passing the monumental EUR, the district ideated by the Fascist regime to host the 1942 World Expo which never took place.

Beyond this wide avenue, the walls regain their steady and imposing layout, but the long series of towers that have dominated for the last couple of kilometres is broken by a majestic wall rampart of the Papal era: it is 300 meters long and was designed in the 16th century by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger to better protect the south of Rome from a likely Turkish invasion. The work is marked by the coat of arms of Pope Paul III on the peak’s corner.

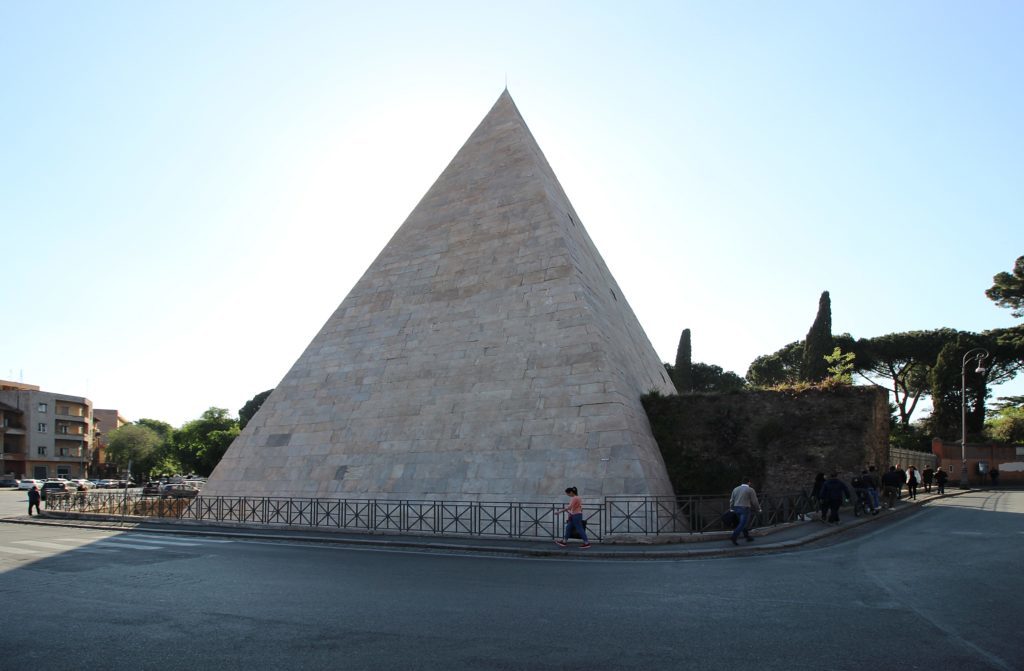

The walk continues through the quiet residential area of San Saba, named after an ancient monastery which was founded in the 7th century by escaped monks from Mar Saba in Jerusalem. During our long urban trek through Rome you may have noticed that serenity and peace is often an island in a sea of noise and chaos. So back to the traffic madness we go! You have the last gate, Porta San Paolo (Roman name: Porta Ostiense), and its exotic neighbour, the Pyramid of Cestius, in sight. We are at a crucial junction of the city as the road coming from the ancient port of Ostia, Via Ostiense, enters Rome here. In modern times, a local train was added that starts here and runs parallel to the aforementioned road, the metro and a large railway station that connects the Capital with the Tyrrenian cities like Pisa and Genua.

The latter has a particular history: Roma Ostiense was only a small countryside stop, but in 1938 it was transformed into a major terminal for the sole purpose of hosting the train that brought Adolf Hitler on his official visit to Rome. The monumental architecture was to provide a “worthy” welcome for the Führer, and the street linking the station with Porta San Paolo was even renamed “Via Adolf Hitler”. After the war this same street was renamed after the Ardeatine Caves, where 335 Italians were killed in 1944 as a reprisal by the German troops.

There is also a smaller station, Roma Porta San Paolo, terminal of the Rome-Lido railway, which is sort of “Via Ostiense by train” – it brings you to the seaside much faster than the congested road, but with dirty and broken-down trains. Luckily, this blemish does not translate into the station itself, which resembles a small art-deco temple decorated with fine murals inside. Next-door, you can visit an open-air museum dedicated to urban and local railways. Here, volunteers of Rome’s public transport company ATAC take care of beautifully restored old trams and small trains that served the city and its suburbs during the twentieth century.

Then you arrive at the “classic” monuments. The pyramid doesn’t come from Egypt, but it is the self-celebrating tomb of Gaius Cestius, a magistrate who lived in the 1st century BCE. Building pyramids for tombs was not uncommon during that period: after Rome conquered Egypt, a true vogue spread among the rich and many funerary pyramids were erected. Cestius’ Pyramid is the only survivor of this “funeral trend”. In 2017, the impeccable restoration of the pyramid received a EU Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award.

In front of it is Porta San Paolo, the last of the “great gates”, named after the Basilica of Saint-Paul- Outside-the-Walls, located 2 km south of the gate. Inside is a museum dedicated to the Via Ostiense, where you can see many archaeological artefacts discovered along this road. The towers host realistic models of the ancient Ostia and its ports. Porta San Paolo was a protagonist also in recent times, and gave its name to a historic battle which took place on 10th September 1943: the Italian Army’s final resistance against German occupation. During this battle, the Aurelian Walls were used for the same purpose the Emperors built them so many years ago, but despite the courage of the soldiers and the first partisans, modern warfare equipment proved too effective.

The Aurelian Walls continue their route to the Tiber and terminates in Testaccio, which has been a working class neighbourhood for quite a long time as its river harbour was active from the Roman age until the XIX century. The name is derived from the Monte Testaccio, a hill created by shards of jars unloaded by the ships at the port during the centuries, but it is also called Monte dei Cocci (Mount of Shards). After the port was closed down, modern industries like the gasworks and the giant slaughterhouse attracted thousands, maintaining the working identity of the area that is slowly being eradicated through a process of gentrification today.

Our final stop is the monumental former slaughterhouse. It covers a wide area of Testaccio and served as the main meat supplier for Rome between 1890 and 1975. Despite the functional destination of this structure, the architects gave it a very monumental look: the entrance is a big gate above which a winged genius knocks down a bull. The buildings inside were designed and neatly placed according to hygienic and functional principles, forming a small “meat town” complete with streets and (slaughter)houses for each kind of animal. Today this “village” is alive again and one of the hearts of Rome’s contemporary culture. Here you can find the Architectural Department of the Third University, a detachment of the MACRO (the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome), and the Pelanda, an exhibition hall where pigs were once skinned. The place has played also an important role in the Italian gay culture.

We have now reached the river Tiber. The Aurelian Walls used to extend onto the opposite bank, but Pope Urban VIII decided to replace them with a more modern structure, the Janiculum Walls, in the XVIII century. Who knows, perhaps these will be the protagonist of our next urban trek through Rome.