A current trend within the field of cultural heritage is a larger focus on environmental challenges and sustainability. One aim is to highlight how cultural heritage education and research can challenge the nature-culture divide and help create a more holistic understanding of the world. To understand how nature and culture are connected, not opposite and competing, we might start by looking at obvious links that have important roots and functions in both camps, for example trees. Trees are obviously part of the non-human natural world, but looking at the cultural heritage from all over the European continent and beyond it is obvious that the celebration and mythical importance of trees, as well as the trees’ functions for construction and food production are also a crucial part of our cultural foundation. To illustrate trees’ importance in our shared European cultural heritage this article takes a look at how these life-giving plants have affected history, culture and the imagination of people in Scandinavia, Britain, and Greece.

The world tree and the sacred trees of the Vikings

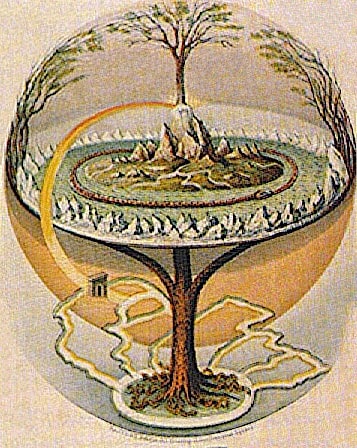

The world tree, also referred to as the tree of knowledge or tree of life, is a classical image in many religions and philosophies from around the world, which often depicts the tree as a centre pillar that connects the underworld, the known world, and the heavens. In Norse religion and mythical tradition this tree is known as Yggdrasil and played a crucial part in the cosmology of the ancient people in the most northern parts of Europe. There are differencing written sources and theories about the reality and symbolic value of Yggdrasil. However, it is widely accepted that the cosmic tree was believed to be an Ash tree.

An important story containing Yggdrasil is the myth of when Odin hanged himself in order to gain knowledge of the runes, the alphabet and sacred symbols used for divination in the north. This is also connected with the ash tree’s association with wisdom, knowledge divination in folk belief, which made the ash a sacred tree for the Vikings, sometimes referred to as “Aescling” meaning ‘Men of Ash’, and also other people in northern Europe. The ash tree and trees in general were also important in the mythology directly connected to humans. The Vikings and their predecessors believed that the first humans, Ask and Embla, were shaped and created from wood before being given life by Odin and his brothers. Ask was created from an ash tree while Embla’s origin is more discussed though many argue that she seems to originate from elm.

In addition the trees’ significance was visible in the everyday life of people and in the Norse tradition sacrifice rituals. It would have been normal for every farm to have a “tuntre” (farmtree), which was important to uphold order on the farm and protect people and animals from danger. The tree was often planted on the burial site or mound of the founding father but later also in the middle of the farmyard. The tuntre was a local representation of the Yggdrasil tree and people sacrificed to the tree so that it would hold control over the “cosmos” of the farm in the same way the Yggdrasil upheld order in the entire universe. Trees were also an important part of the ritual sacrifices called blot, when the blood from the sacrificed animal would have been smeared on trees and pillars to please the gods and goddesses.

In addition to sacred trees belonging to every farm and the private sphere, there were also some more important trees of public religious value. In Scandinavia the most famous was the Sacred Tree of Uppsala. The tree is believed to have stood next to the temple of Uppsala, one of the most important sacred sites in Sweden before the transformation to Christianity. Adam of Bremen described the site in his work Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum in the 11th century CE, and put emphasis on the importance of the tree. It is believed that ceremonies and sacrifices, potentially human sacrifices, were held in connection with the tree and the spring next to it. As many argue that the tree might have had strong connections with the idea of the Yggdrasil tree, the sacrifice could have been inspired by the story of Odin hanging himself from the branches of the sacred tree.

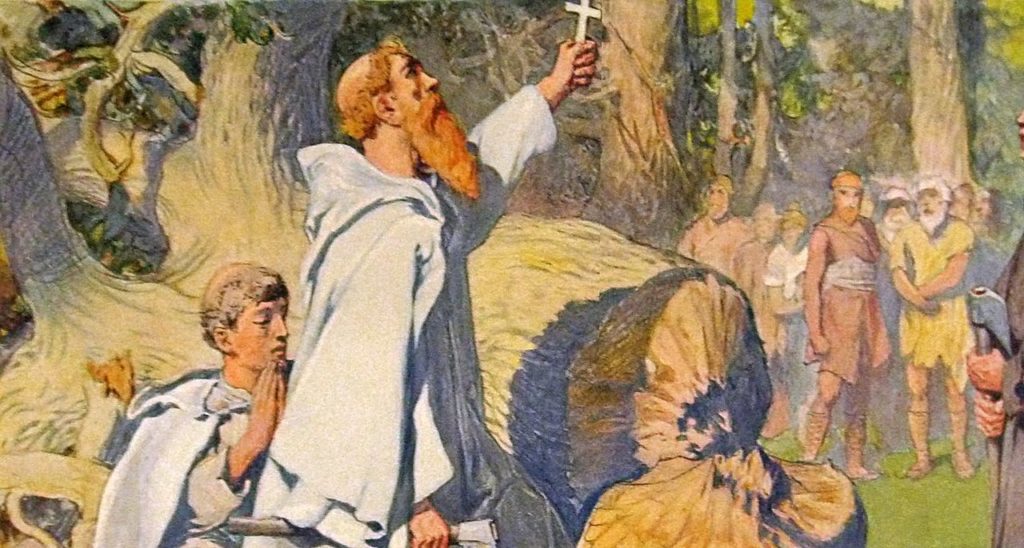

This type of divine worship of trees is not only known from the times of the Vikings and the Scandinavian people but also from the older Germanic traditions on the continent. Some of the most well known of these sacred trees or poles were the Donar’s Oak, dedicated to Thor, and the Irminsul, which is believed to have been cut down by Charles the Great, King of the Franks (r.768-814 CE) during his crusades against the Saxons in the 8th century CE. An important part of the spreading of Christianity amongst the Germanic people was to cut down these sacred trees, so that the pagan believers no longer would have a place to worship their old gods.

Sacred oaks, hawthorns and apple trees

Sacred oaks are however even more associated with the mysterious druids, who today are more connected with the ancient people of the British Isles, even though they are also known to have been present on the continent in Gaul. The ancient Romans described the druids as powerful and wise priest of the Celts, but their exact identity and function is hard to pinpoint, as the source material is inconsistent. However, their link to sacred oaks and groves in general has fascinated researchers and new religious communities for centuries, and is also important in the British national romanticism of their ancient past. It is believed that the oak tree played an especially important part in the religious practice of druids and a widely accepted theory is also that the name druid means, “knowing [or finding] the oak tree” in Celtic. In Pliny the Elder’s descriptions of the druids, he describes the Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe. In the ritual the druids are said to be climbing a sacred oak and collecting mistletoe berries, which they used for medicinal purposes and possibly to access spiritual roams. The oak might have been one of the widest celebrated trees in Europe in ancient and pre-Christian times and considered sacred amongst many different cultures across the continent. For example, the Greeks also considered the oak to be of special importance, where they consulted the oracle Dodona, second only to Delphi, which was located in a sacred oak grove.

There are also other trees present in British myths and stories that are an important part of the island’s cultural fabric. One of the places where the link between nature and culture and the celebration of trees are most visible is in the mysterious town Glastonbury in Somerset. Glastonbury is a site linked to several myths and legends, including that of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table and that of Joseph of Arimathea who supposedly brought Christianity to England. In both these legends trees play a vital role and are still celebrated by locals and visitors coming here from all over the globe.

The story of Joseph of Arimathea is linked to the sacred thorn in Glastonbury. Joseph is believed to have been a rich trade merchant and disciple of Jesus who brought the Christian faith with him to Britain after becoming a missionary. On his travels he brought a pilgrimage staff and when he placed it on one of the hills in Glastonbury it took root and became a blossoming thorn, which Joseph saw as a sign for where he to build his church – and hide the Holy Grail (which is another legend). The Glastonbury Thorn is still considered a sacred tree and the original tree has been propagated many times. One tree is standing at the original spot of the “Sacred Thorn” at Wearyall Hill, though unfortunately it was deliberately damaged in 2010, and some of its sister trees are standing at different sites in the town, including one on the grounds of The Glastonbury Abbey. These thorns are a special variety of hawthorn that blossoms twice a year, on Christmas Day and during Easter. It is a royal tradition for one of the schoolchildren in town to cut a flowering branch of one of these sacred thorns every Christmas and send it to the Queen for decorating her Christmas breakfast table.

On the grounds of the abbey and in the wider Somerset Levels region in general, you will also see another three that is much celebrated: the apple tree. The tree is important for the region’s production of apple cider, but in Glastonbury it also connects the site to the mystical land of Avalon from the Arthurian legends. Some argue that Avalon means island of the fruit or apple trees and that the name thus connects Avalon to Glastonbury. According to believers, Arthur was brought to Avalon, after being wounded in the Battle of Camlann. His supposed burial site can be visited at the Glastonbury Abbey, and has been a site for pilgrimage ever since the monks discovered his lost tomb during the 12th century CE. However, his remains, together with those of his wife Guinevere, are believed to have been moved during Henry VIII’s reformation of the church of England. Therefore, there is no way to prove if Arthur really was laid to rest in Glastonbury, and now only the apple trees are left as a token of the legends that supposedly took place here in a veiled and mysterious past.

The goddess and the olive tree

Further south in Europe, another tree is widely celebrated and considered sacred since ancient times: the olive tree. Crucial for cultural and economic development all around the Mediterranean, the tree also possesses a sacred and mythical dimension, and this is possibly most visible in Greece. Athens, the centre of the ancient Greek world, was the city of the goddess Athena and the myths tell us that it was the olive tree that made the Athenians choose the goddess of war, fertility and wisdom as their protector. Athena competed with Poseidon over the favour of the people of the new rising city and they each presented the people with a gift. Poseidon created a spring of saltwater at the Acropolis, while Athena created the olive tree and gifted it to the people. The people chose the olive tree, which thereafter became a fundamental ingredient in their culture and civilisation, both in terms of cooking, construction, and celebration of kings and athletes, and the city celebrated the goddess by taking her name. Today a moria, which is an especially important and sacred olive tree, stands on top of the Acropolis, a descendant of the original tree gifted by Athena, symbolising the city’s close relationship with the goddess and the importance of the tree in Greek culture through time.

On Crete, it is also possible to visit some extraordinary olive trees and learn about another myth connected to sacred trees. One of the oldest olive trees in the world is believed to be located at the island, the Olive Tree of Vouves. The monumental tree is possible to visit and go inside the trunk and roots which it is popular amongst tourist from all over the world. The exact age of the tree is not determined, but it is believed to be several thousand years old – yet it still produces new olives every year. The tree is also celebrated by the local inhabitants and serves as a symbol of the importance of the olive tree for the Cretan society, culture and economy. The Secretary General of the Region of Crete also listed it as a natural heritage monument in 1997. However, there are also several other ancient olive trees on Crete highlighting the close connection between the natural environment and culture on the island where the first European civilisation developed. Some of the trees worth visiting are the Azorias olive tree, the great olive tree of Aerinos, the Grambela olive tree and the ancient olive tree grove at Gortyn. At Gortyn, you can also visit another sacred tree connected to Greek myth, the rare evergreen plane tree.

The legend tells us that the founder of the Minoan civilisation on Crete, King Minos, was the son of Zeus and Europa. Europa was a Phoenician princess who Zeus kidnapped in the shape of a bull and brought to Crete. Zeus and Europa then consummated their relationship under the plane tree, sometimes described as rape, other times as a loving consensual affair. The union brought three sons, including King Minos, and the tree became blessed and has remained evergreen (unusual for this species) ever since. The tree is still standing today in the ruins of the once powerful city of Gortyn and is continuously celebrated as a site of cult practise.

As we have now learned, trees have for a long time been celebrated by humans and played an important part in the development of cultures and civilisations. Maybe by also appreciating the cultural aspect of plants and the non-human environment we could (re)learn how to connect more deeply with the natural world around us as our ancestors did in the past, and take care of our planet so that she might continue to thrive and create new life.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX