by Rea Terzin

I hated medieval Serbian art. I can still vividly recall that dreadful feeling after failing my exams. The professor’s sour face haunted me for a long time after I told him that the left side of the second zone of the west wall depicts the Dormition of the Virgin Mary scene, not the Crucification of Christ. The fresco programme within the Serbian medieval churches is so rich that I either have time to read it all or the mental agility to remember all the scenes on each side of each wall (and each detail on each scene).

But even with due respect to major historical buildings, approaching the subject from a time distance, whether it traces to ancient, medieval, Renaissance or contemporary sources, creates certain patterns of more thematic exploration. Rather than immersing ourselves in tons of books that are extraordinarily thorough in their historical research, it is sometimes more insightful to feel the “life” that permeates through art itself.

The sharpness of the picture of stylistic evolution, building types, individual entities of architects or full creative dimensions specific to one period does not result mainly from research, interpretation, and critical imagination but rather from the close relationship of a researcher and subject — my initial reaction to the fresco paintings within Saint Mary church on Maligrad island in Albania was, therefore, surprise and gratitude. Soon enough, I began to admire the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, that hateful scene that had caused me to fail my exam.

My scant interest in the development of medieval Serbian art turned into appreciation and eagerness to acquire new knowledge. All of this has strongly affected my perception and I am no longer content with knowing merely the static facts of buildings, artists, or places; I want to learn about all processes that brought them into being and that underlie and structure their never-ending process of interaction.

To “see” art, we must have direct contact with the past. An art piece is then a particular form of fiction, one which exists in the present and might be used to grasp the essence of what we believe lies beyond. And after an initial blindness comes seeing something deeply for the first time.

European Heritage Volunteer Project in Albania

This is the story of the small church of Saint Mary that is hidden under fig trees on the island of Maligrad in Albania. At some distance of 150 metres from Great Prespa lake, the church sits in the southeastern cave or, viewed from the direction of the lake, on the viewer’s right-hand side, above the water level.

Church of Saint Mary is notable for its 14th-century frescoes, which used to completely adorn both interior and exterior walls. It is believed that Serbian nobleman Kesar Novak, who held the region of Lake Prespa during the Serbian Empire of Uroš the Weak (1355-1371), built the church.

The European heritage project called “Conservation works at cave churches and documentation of frescoes” aimed to create technical documentation of frescoes so that committed conservators can determine the degree of intervention that should be carried out and return the valuable fresco paintings to good condition. To successfully take part in this project, we had to have an extensive understanding of the technical and historical nature of frescoes and of the painters’ materials.

Conservation offers the architectural historian an ideal medium for a number of approaches and widely varying purposes. On the practical side, art history and conservation combined are extremely useful in focusing extensive research and organising the results.

Under the guidance of experienced restorers-conservators from Northern Macedonia, Switzerland and Croatia, we were honoured to learn the complete process of documentation, conservation and restoration of frescoes. Divided into two groups, we worked in two cave churches on the eastern shore of the lake. These cave churches hold highly valuable frescoes dating back to the 14th century that have become endangered as a result of neglect, decay, and climate change.

In the following sections, I will reveal the fresco programme and the working process.

The Fresco Programme of the Interior Western Wall

The works started with detailed documentation of the frescos. The fresco programme in the left lower part of the western wall depicts the figures of the Holy Emperor Constantine and Holy Empress Helen. On the right side of the wall are two female saints, unidentifiable due to severe damage. The two side walls adjacent to the door present cross symbols and decorative patterns.

The left side of the second zone of the interior west wall depicts the scene of The Crucification of Christ and the right side depicts the scene of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary. The arched segment at the top depicts the scene of the Resurrection, one of the miracles of Jesus Christ.

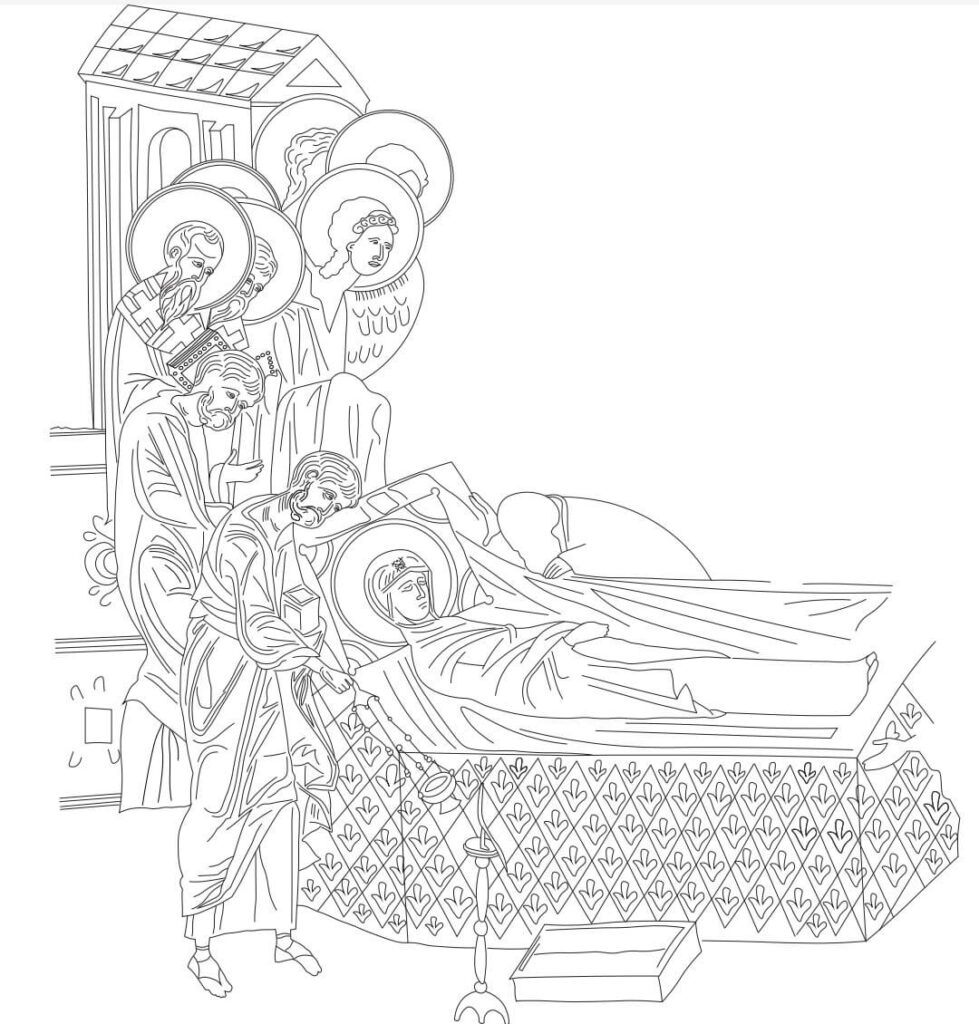

A fresco depicts the scene of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, framed in a simple red border. The focal point of the composition is the Virgin Mary laying in her deathbed. Christ, depicted as a small child in swaddling clothes and encircled in a mandorla, is seen carrying the Virgin’s soul to heaven. Above him is a cherub, a winged creature, and on both sides is an inscription in white letters on a blue background. Stylized architectural buildings are depicted in the background, to the left and right upper corners. Christ’s initials are inscribed on the right and the left side of his halo

In the left part of the scene are figures of the apostles, archbishops, and angels. The apostles stand in the first row, the archbishops in the second and the angels in third. Two archbishops (one cannot be seen clearly) wear robes of an archiereus – a sticharion and a white omophorion with dark blue crosses. In their left hands, pressed to their chest, they hold decorated Gospels.

Strong lines prevail among the robes of each figure and short and swift brush strokes are used to make white highlights on the skin. Around the fine contours of their faces, the painted layer demonstrates a skilfuldraughtsmanship through modulation and the use of greenish shading. Precise drawings with an outstanding attention to detail characterises the personal style of this artist, which results in adequately proportionate figures.

Working Process

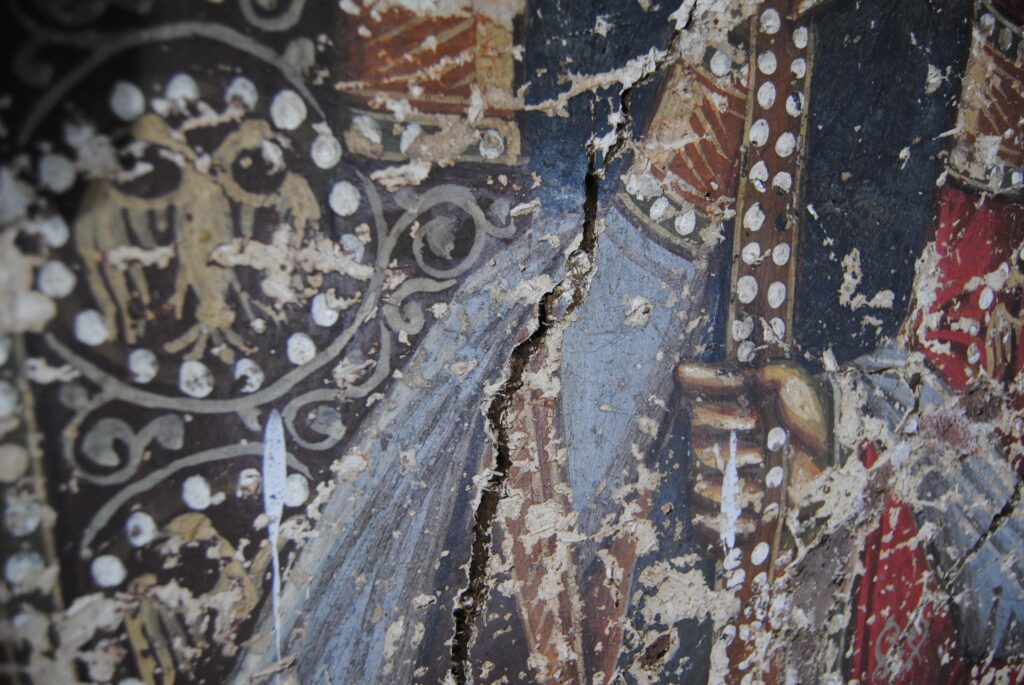

The most important aspect of developing a conservation strategy is assessing and analysing the nature and causes of damage. The conservator can only make appropriate decisions based on proper documentation in order to reduce or eliminate the damages, as well as to determine how to prevent future ones.

Our process of documenting the frescoes of the western interior wall of the Saint Mary church involved creating data on the state of conservation, including:

- data on damage to the support (wall structure, intonaco, etc.)

- damage to the paint layer

- extraneous substances present on the painted surface (dust, soot, etc.)

- evaluation of previous restorations

Data on the painter’s technique, including:

- giornate

- colour stratigraphy

- sketches

Does the artist’s modelling go from dark to light colours or from light to dark colours resulting in partially thin layered surfaces? Where exactly can partially missing parts of the paint layer be seen? Have the previous restorations altered the original appearance in any way? All these questions helped us to reflect critically on the frescos.

Identifying damage and its underlying causes was our main focus. In addition, we had to look deeper into colour stratigraphy as part of the painter’s process and determine if, for example, colours deteriorated over time.

We also had to find giornate and explain if they are extremely large or of standard size relative to the dimensions of the frescoes. We noticed a lot of badly applied repairs to the support that caused damage to the paint layer.

Giornate is an Italian term that refers to the incremental sections into which a fresco painting is divided for easier execution. Each “giornata” is painted while the plaster is still wet, allowing the pigment to bind with the surface and become part of the wall itself as it dries. This technique is commonly associated with fresco painting during the Renaissance period.

For example, in Michelangelo’s famous fresco painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, each scene or group of figures is often composed within a single “giornata.” This division allowed Michelangelo to work methodically across the vast ceiling, completing one section at a time.

Although for the most part we focused on analysing damages, we also had to define the materials the intonaco and the arriccio were composed of. To treat the frescoes properly, thoroughly addressing all questions with incisive attention to detail, we had to determine the average thickness of both of these layers, as well as to find stencils that the painter made before the actual painting process began.

What sparked a wave of interest was the moment when our coordinator Ivan Vanja found the spots in the centre of the figures’ halos, which proved that the artist used a drawing compass.

We also helped set up the scaffolding – a task which was indeed demanding. This installation process was a great insight into the project’s unpredictable nature and how demanding it is to create technical documentation. Not only did this project require preventive conservation knowledge but also physical readiness to assist with the scaffolding in order to proceed with the next phase: documentation of the upper zones.

Our coordinator supervised the erection of the scaffolding to ensure the optimal working distance from the painting surface and to avoid damage caused by careless handling. By using scaffolding that concealed only a part of the vault, we were not exactly in the most comfortable position, but it was an experience that brought us joy (and “can’t stop laughing” moments) and taught us to be prepared for any unexpected task.

Having completed our technical description, the next step was to assist our photographer Nillo with lighting while she took photos in the dark church interior. The frescoes on the ceiling required a far stronger light, so we had to do our best and move the light to the proper position.

The next step was to freely choose points within the fresco composition and take accurate measurements of them so that rectified images could be done successfully. These rectified images were important as the pre-phase of the next documentation stage: drawing fresco compositions in Adobe Illustrator.

Before this, frescoes were drawn on a transparent plastic film and transferred onto a computer, where they were matched with photographic documentation; using the rectified images, we were able to draw the lines of the fresco compositions and print them out; then the damages were observed and documented. Following that, the frescos were conserved by filling cracks with grouting mortar based on crushed limestone from the shore of Great Prespa Lake.

Finally, incisions created by vandalism were closed and retouched. In my experience, drawing was the most challenging, yet inspiring phase of the project. It is surprising how the full creative dimension of each individual can arise in an inspiring group, as well as what can be done within only two weeks.

Focusing closely on a single 14th-century fresco detail, not only was I fortunate to travel back in time and feel the way painters used brush strokes, but I also got a better insight into the pinnacles of Serbian culture and art across our border.

Hopefully, this project will provide a reliable basis for future conservation work focusing on the fresco programme of Saint Mary’s church.

If you wish to contact the authors of this article, please send an email to community@europeanheritagetimes.eu