Art is everywhere, even in the trenches.

From time immemorial the human primordial needs creation, using all his creative potential, knowledge and skill to express himself through some form of visual art. Man’s designs can be found and seen everywhere. Even in the most unexpected places and time, where our common sense tells us they do not belong, as in times of sickness, conflict, and war. One proof of the previous statement is the collection of Bitola Мuseum in North Macedonia. Upon examination, one can notice unusual household items found in the ethnology department. Namely, these peculiar objects represent vases that were part of the decor and interior design of the homes of Bitola aristocracy up until the middle of the previous century.What is uncommon about them is the material that they are made of and the very way of their making. Precisely, these vases were made by soldiers or prisoners of war in the World War I out of unexploded bombshells. They are part of an art genre, widely known as Trench Art, or sometimes Soldier Art.

Trench Art is a form of art that was common during the First World War (1914-1918) and is not specifically related to one place or one ethnic group of soldiers. It goes by that name because of the dug trenches, where they fought the battles. Trench Art was present throughout all war zones and fronts. It can bluntly be said that it is one sort of shared folk art, European heritage in a broader sense.

Therefore, the main question is: How this kind of heritage came into being. Why were these vases made in the first place and how did they end up in the homes of Bitola bourgeoisie as part of their rich furniture? Part of the answer to the first question is in the aforementioned man’s primordial need for self-expression through the creation and his universal artistic trait, regardless of the circumstances in which he finds himself. The other part lies maybe in the conditions in which these particular vases from Bitola Museum were created.

World War I is notorious not only because of its dug trenches but also because of its air campaigns. One of the most well-known fronts during the war was the Macedonian or Salonica front. It was formed in 1915, as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia against the combined attack of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria. This front passed through the city of Bitola, which was one of the biggest and wealthiest cities before the Balkan Wars, also known as Monastir, the administrative and military center of Ottoman Rumelia. Unfortunately, after the First World War Bitola was declared a city of suffering. A city of war and destruction that had been professed as the second most bombed city in this Great War, after the city of Verdun, France. For that reason, it was also called the Balkan Verdun and afterward, it was awarded the Order of the Military Cross of the Republic of France. The estimated number of grenades that were dropped over Bitola is around 8600. How many of those grenades or shells were converted into the beautiful vases today can never be known. Paradoxically, the more air bombing, the better creations and “bombastic” decor.

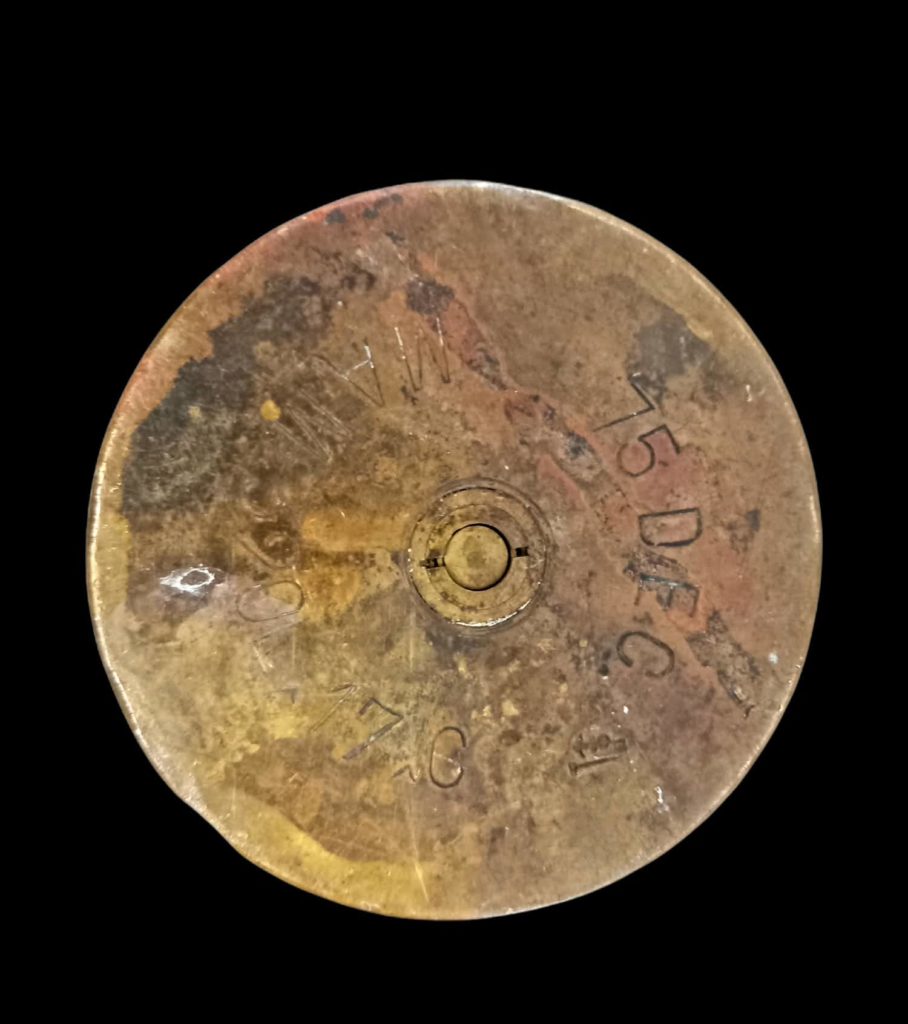

One can only assume in which way existing amid that kind of suffering and misery affected the soldiers in the trenches. Living in constant fear for their lives in terrible conditions such as extreme climate changes and diseases such as dysentery, typhoid, malaria, typhus and diarrhea. When the reality is so painful and unpleasant, the individual usually turns to escapism. And what better escape from reality than art itself. A sort of a beautiful mask for all the wretchedness of the war, mask for the dreadful grenades.When analyzing the above-mentioned ornamental museum items, different styles can be noticed. However, the manners of decoration and ornamentation are the same. Besides, all of the vases still have their serial numbers imprinted on the bottom from their production in ammunition factories.

Engraving, tanking and embossing techniques were used on all of them, made with tools available to the soldiers, usually everything that was on disposal on the battlefield.

The dissimilarity lies in the depicted stories on them. Generally, geometric and floral decoration is present, as well as heraldic symbols, architectural elements, women, and muses.

But, the most impressive ones are those who tell whole tales of travel, love triangles and quadrangles and battles.

All of them are exceptional in their way and represent one kind of sophisticated folk art. Every artist, or in this case soldier, had his own story to tell. Something that in that moment was significant to him, missing or something he thought should not be forgotten. One example is the portrayed Battle of Kaymakchalan on several of the vases which is considered the bloodiest and cruelest battle fought on the Macedonian front with losses more than 15,000 soldiers and as many wounded.

In general, military history is written from far away, by historians who were not directly involved in the war itself. In this case, those who made the history, are the ones who tell it through their art. Each vase is a first-hand story. By trading their narratives with the local population of Bitola in exchange for food, clothes, etc. the tellers (soldiers) made those narratives immortal. Through enriching the interiors of Bitola aristocracy these mementos of war became part of Bitola’s rich ethnological, historic, and military heritage.

Artistic expression is one of the highest forms of self-expression. Out of every evil derives something good and beautiful. Even in times of war and destruction, art is man’s “best friend”, shred of hope and a way to push him through all the hardships into a better future. And after all, is said and done we can declare that art and beauty will win the war and save the world, eventually.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX