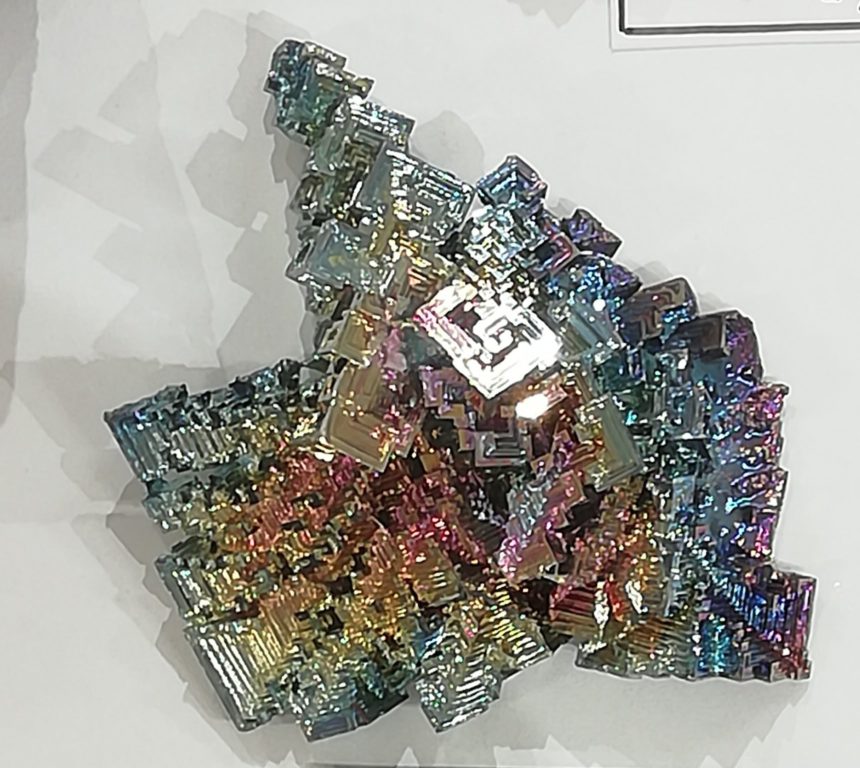

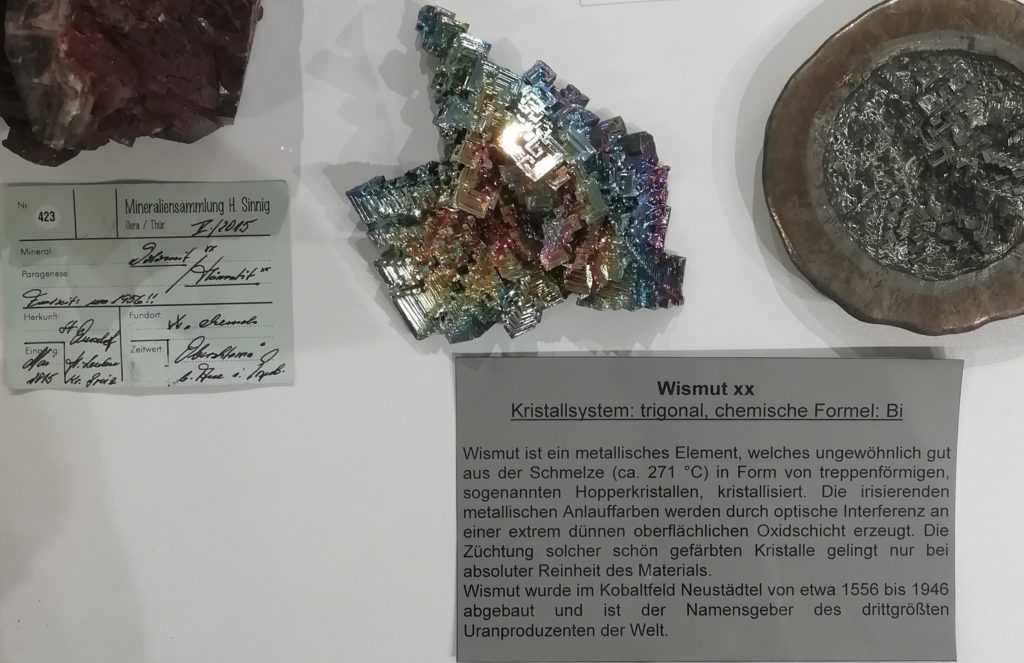

We would not have known the reason behind the nebulous meanings and definitions of wismut in Bad Schlema in Saxony region, if we would not meet a man in the Uranium Museum (Uranbergbau, The Museum of Uranium mining). This story might also enlighten you about the origins of the name of Wismut Company in East Germany, which is still active in the region for the current industrial activities. Wismut is the German word referring to bismuth, which is a chemical element with the symbol of Bi.

The man’s words about the uranium mining industry in the Ore Mountains while he was explaining the historical stratifications of the mining minerals in this region were quite surprising. He said: The man’s words about the uranium mining industry in the Ore Mountains while he was explaining the historical stratifications of the mining minerals in this region were quite surprising. He said: “We sadly discovered the uranium.”

It was known that uranium was previously mined, though it was mostly used for decorative purposes, such as for the famous uranium glass or chinaware that was produced in the Czechoslovakian part of the Ore Mountains. In fact, the former miners of Bad Schlema already knew that this black mineral — usually attached with the silver and cobalt ores — could be extracted during the silver and cobalt mining process, as described by German mineralogists and chemists in history. It was also known that this unique mineral was different from the others within the mineral family as it might cause cancer due to radon, but this was not taken seriously by the miners due to the small quantity of the cases among an already-hazardous industry.

Wismut or the Mineral A9 that makes Bad Schlema ‘The Second Manchester’

This mineral has been the greatest paradox in world history: while it was the raw material of the radon gas that killed many people, on the other hand, it was also a kind of counterpoison via the radon spas. In the 1920s, the fame of the radioactive mining waters of the region had come to the fore through the Bad Schlema’s Radon Spa, where people come not only for treatment of diseases but also for socialisation purposes.

In the 1940s, people started to become sick due to this mineral which made it ‘special’ in the industry. Yet the word ‘uranium’ was never used by the former miners in the Ore Mountains area in Saxony, where the first industrial uranium deposits were mined in the world. From the 1920s until 1949, several radon spas in the region, including the one in Bad Schlema, caught the attention of the Soviet Union, especially during the interwar period when the region became one of the recovery places for uranium mining. It became a kind of hopeful place for lots of people to recover from the damage of the war.

In fact, the region became a secret project, and ‘uranium’ was a banned word that was covered by ‘wismut’ or ‘the mineral A9’ to hide the radioactive potential of the place — a new potential goldmine for the industry. The industrial importance of the place gave lots of hope to many people until the beginning of the 1990s despite its physical and environmental consequences. Despite the destructive impact of uranium mining on the environment and the great number of deaths, it also brought ‘richness and wealth’ to the mining region. For example, Bad Schlema was considered a ‘second Manchester’, as a place of hope for many people, since the mining industry offered employment and welfare for the people after the war period.

Interactive relationship: the industry, people, and place

The Erzgebirge region is a complex landscape consisting of various veins that represent different industrial milestones in history through a various number of discovered minerals. The landscape itself holds a kind of magic that has not only guided humankind to shape their living environment but also led industrial evolution. Thus, the outstanding landscape of the mining industry in the region provides an extraordinarily comprehensive picture of the relationship between industry, people and place, which has been continuously adapted according to the era’s socio-cultural context.