By Lianne Oonwalla, an Indian student in Germany.

Continuing the theme of “Spooktober”, Part Two explores the ancient Celtic origins of October’s favourite holiday. Read Part One here.

Shadows of a thousand years rise again unseen, voices whisper in the trees, “Tonight is Halloween!”

Dexter Kozen

Picture this: a crisp October morning, fog drifting eerily over the lawns of an abandoned castle in the countryside…you take a deep breath and an ethereal charm falls upon you; you can almost feel the premise of something supernatural lurking around the corner. Your imagination goes into overdrive…a shadow here, a misty figure there. You hear a sudden howling as you enter the castle hall, the cold wind wailing through it’s empty corridors. Well, you hope it’s the wind and not the resident ghost! Hesitantly you take another step, the castle’s dark rooms beckoning you closer. What secrets does the castle hold? Only one way to find out…and now that we’ve set the scene, let’s dive straight into the spookiest of all spooky stories: the origins of Halloween.

The wheel of time

It is a little known fact that Halloween tradition is actually rooted in an ancient spiritual ceremony practiced by the Celtic tribes of Northern Europe. Samhain (pronounced sow-win or sah-win) was a Celtic festival that began around 2,500 years ago (as dated by Ancient History Encyclopedia), and can be considered the predecessor of the modern Halloween festival.

The Celts were a collection of tribes that spread over much of central Europe, notably in Ireland, Britain, France and Spain. Much of their culture is still prominent in modern Irish and British society. Their worship was based around pagan beliefs and is often called Celtic paganism. Ancient Celtic religion placed importance on the concept of “in-between” or transitional periods. Their religious celebrations were affected by the calendrical structure existing at the time: the wheel of the year. The Celtic year was divided into light and dark. Each phase was marked by two festivals respectively: Imbolc, between the winter solstice and the spring equinox; Beltane which fell between the spring equinox and the summer solstice; Lughnasadh, the season between the summer solstice and fall equinox and Samhain, the time between the autumn equinox and winter solstice.

Of the four festivals, Samhain was considered the most important as it was regarded as the Celtic new year. The Celts considered these few days to be the mid-point between the autumn equinox and winter solstice; a transitional period between summer’s end and the encroaching winter. Samhain was the time to harvest the remaining crops and prepare for the coming winter. Animals were ushered indoors, either for breeding or sacrificing. Feasts and merry gatherings would be held, debts were settled, people would exchange pleasantries and take care of official matters. Trials were held and justice was appropriately doled out, even kings were elected at this auspicious time.

Everyone’s invited to the party

Samhain celebrations would begin at sunset on October 31st. During the festival, it was believed that the veil between the human and supernatural realms would be at it’s weakest, allowing the living to be be visited by spirits of the dead and ghouls of the “Otherworld”. Ancestors and deceased relatives could cross over and visit their families. Trickery and pranks would be played aplenty, with the guilty sometimes passing blame onto mischevious spirits and fairies. To appease their deities, the people would often make sacrifices of animals and crops, offering them to gods and goddesses to ensure a safe and secure livelihood through the hard winter.

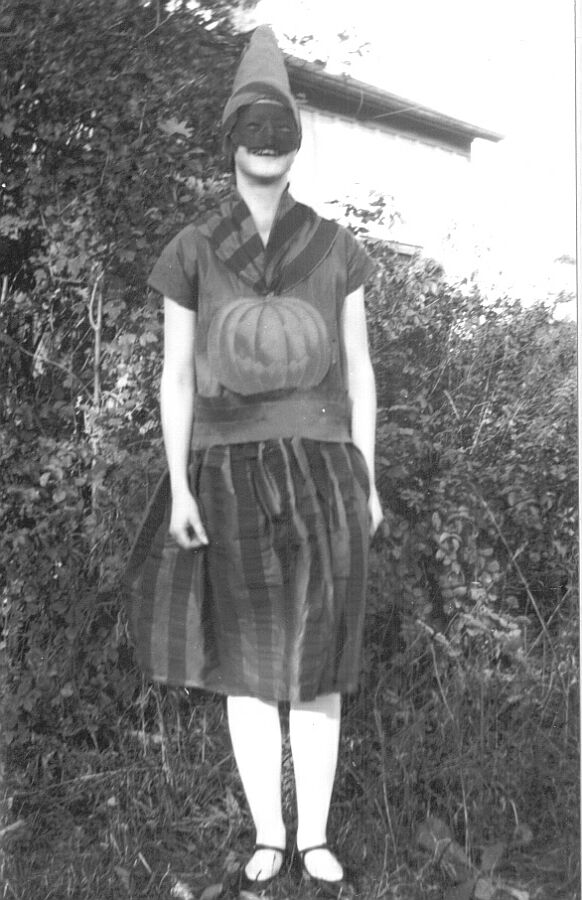

What we know of Samhain and it’s festivities is fragmented. As tradition went, every hearth in every home would be doused at dusk. Druids (Celtic priests) would light large fire wheels and chant prayers around it. Animal bones and other offerings would be thrown into the fire, thus earning it the term “bone-fire” (later evolving into “bonfire”). A burning log of the communal bonfire was carried back to each home to relight the hearth, inviting warmth and light through the cold winter, and marking the start of the festival. Food, wine and offerings were exchanged, communal dinners were hosted and people donned costumes made of animal skin and wore masks painted with ghostly features, trying to fool any spirits who might cause them harm, a practice that was known as Mumming or guising. It was believed that the thin veil between worlds on this night also enabled accurate divinations for the future; Druids would read fortunes and make predictions of what the new year would bring.

The open border invited other ancient creatures to cross over into the living world. Among the spirits and creatures that would visit on Samhain night were the fairies Aos sí, who would wander the village collecting offerings left on doorsteps; the headless Lady Gwyn, dressed in white, who would chase villagers in the night, and the shapeshifting Dullahan who’s common form as a headless horseman was an omen of death for anyone who encountered it. The Druids would regale the townspeople with popular myths and legends, they sang of battles fought and won during Samhain. One of the most popular tales told around the bonfires was the story of The Second Battle of Mag Tuired, describing the epic battle between the Celtic Tuatha de Dannan and the wicked Fomor that took place during Samhain.

Do any of these traditions sound familiar to you? Dressing up in scary costumes, sharing mulled wine by a fire, listening to legends and stories, enjoying food and sweets, and the reading of fortunes…almost sounds like a Halloween party in the 21st century!

A culture transformed

A gradual change in the festivities and practices of Samhain began during the Middle Ages. Communal bonfires gave way to individual fire ceremonies called Samghnagans, shared by one family, drawing in protection over their household for the coming winter. Dumb Suppers were held as an invitation for ancestoral spirits to dine with the living. The table was laid with as many places as the host wished, some filled with living relatives and the rest reserved for visiting spirits. As was the custom during Dumb Suppers, guests ate in complete silence to increase the chances of a supernatural visit.

Games and parades were also a common practice during Samhain celebrations in the Middle Ages. Bobbing for apples was a popular game that originated during this time. Participants were both children and adults, often women, and were blindfolded and had their arms tied behind their backs. The game was to fish an apple out of a bucket of water using only their mouths and teeth. It was believed that the first one to bite an apple would be the first to marry or find a spouse. Jack-o-lanterns also made an appearance around this time. The popular practice of carving turnips or pumpkins derives from the old tale of cursed Jack, a blacksmith who’s deal with the Devil went wrong, thus barring from Heaven. He was expelled from Hell and condemned to walk the earth for eternity. Once, he asked the Devil for some light and was mockingly given a piece of burning coal which he stuffed into a carved turnip to keep the flame alight. People believed that hanging a fire-lit carved turnip outside their doors would keep Jack’s spirit away, and that practice turned into keeping carved pumpkins, lit with a candle, on doorsteps to ward away evil spirits.

Eventually the arrival of Christianity further evolved these traditions into practices befitting the new religious movement. The year 609 AD brought real change to the traditions of Samhain. In an attempt to gain more conversions, the Church began adopting more pagan traditions into Christianity, trying to entice more local followers. Samhain was fused with a similar Christian holiday and May 13th was declared as a day to mourn Christian saints and martyrs, called All Saints’ Day (or All Hallows-day/Allhallowtide), a name coined by Pope Boniface IV. The day before (May 12th) was named All Hallow’s Eve. In the 8th century Pope Gregory III moved All Saints’ Day to November 1st and All Souls’ Day followed on November 2nd, closely mirroring festivities celebrated by the ancient Celts: honouring the deceased, exchanging food and drink, bonfires and even the costume-donning tradition of Mumming was enocuraged.

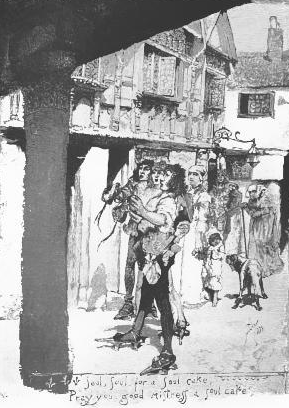

Older customs were also adopted, such as an old English practice on All Souls’ Day called “going-a-soul-ing”. During the annual All Souls’ Day parade in England, children from poorer households would go door to door collecting food, sweets, money or anything else they could get. The pattern was the same: a short song would be sung and an offering received in return. They were often given pastries in exchange for a prayer for the families’ deceased relatives, thus earning the name soul cakes. The practice replaced the old Celtic tradition of leaving food offerings on doorsteps and was taken over by more children every year.

All Hallow’s Eve, which now fell on October 31st, grew more popular than All Saints’ Day. The festivities and celebrations remained relatively stable through the years and were practiced throughout Medieval Europe. Eventually it crossed the sea and arrived in America. It was in early 1800s that All Hallow’s Day transformed into the familiar Halloween as we know it today.

Coming to America

Irish and English immigrants introduced All Hallow’s Day to America during the 1820s, and it was soon adopted into their new societies earning the name Halloween. Celebrations remained the same in essence, but also welcomed newer traditions. Many practices in both ancient and modern form became part of American culture, including Jack o-lanterns, fortune telling, and guising. The custom of going a-souling eventually evolved into trick or treating in 19th century America, which is today the most popular element of Halloween celebrations.

Halloween has become the second most commercial holiday in America and is regaining popularity in a few European countries. Typically, children and adults alike dress up in costumes and go trick or treating around their neighbourhood, receiving candy and other small treats like candied apples and caramelized fruits. Often, front lawns and houses are adorned with spooky decorations, among which are carved pumpkins left out on doorsteps. Pumpkin patches are grown during the season, inviting families to pick out their own pumpkins, and pumpkin carving contests are also the norm during this time. Scary stories are exchanged, horror movies are binge-watched, themed carnivals take place and a general spooky atmosphere reigns the evening of October 31st, worldwide. Rather than only following tradition and the ancient festivities, emphases is given on having a good time.

Cultural trends

Samhain in it’s more traditional form has been celebrated over the years by the Wiccan community. November 1st is regarded as their new year’s day and celebrations begin at dusk on the day before. Divinations are made, Tarot cards are read and predictions are cast, just as they used to be around the ancient fires. Some Wiccans also honour the old festivities like Dumb Suppers. Many other cultures have festivals similar to Samhain or Halloween; for example Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrated in Mexico on November 1st and 2nd. The festival draws from ancient Aztec and Toltec traditions. Contrastingly, they celebrate the deceased and their lives, as opposed to the Celtic practice of mourning and honourng them. It is a celebration of life and not death.

When black cats prowl and pumpkins shine,

A quote by allwording.com

When shivery shivers run down your spine,

When ghosts and goblins ring the chime,

Beware and be scared – it’s Halloween time!

Halloween festivities in the 21st century, in whatever form they take, may not be true reflections of Samhain’s ancient traditions, but they are keeping the ancient customs alive in a manner of speaking. The old ways, just like the souls of our dearly departed, are never forgotten, especially so on this day of the year. So tonight let’s raise a glass in honour of the dead and a second to celebrate the living. Happy Halloween!

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX