Ultima Cena per Immagini, a tale through the photographic archives.

By Silvia Demetri

an architect from Italy

“O quanti grandi edifizi fieno ruinati per causa del foco! Dal foco delle bombarde!”

“O how many great buildings will be ruined by reason of fire! The fire of great guns!”

Leonardo da Vinci

On 2nd May 1519 Leonardo Da Vinci died in Amboise, France. Five hundred years after, in 2019, Leonardo’s year was celebrated all over the world with the most diverse events and Milan, one of Leonardo’s cities par excellence, could certainly not be outdone.

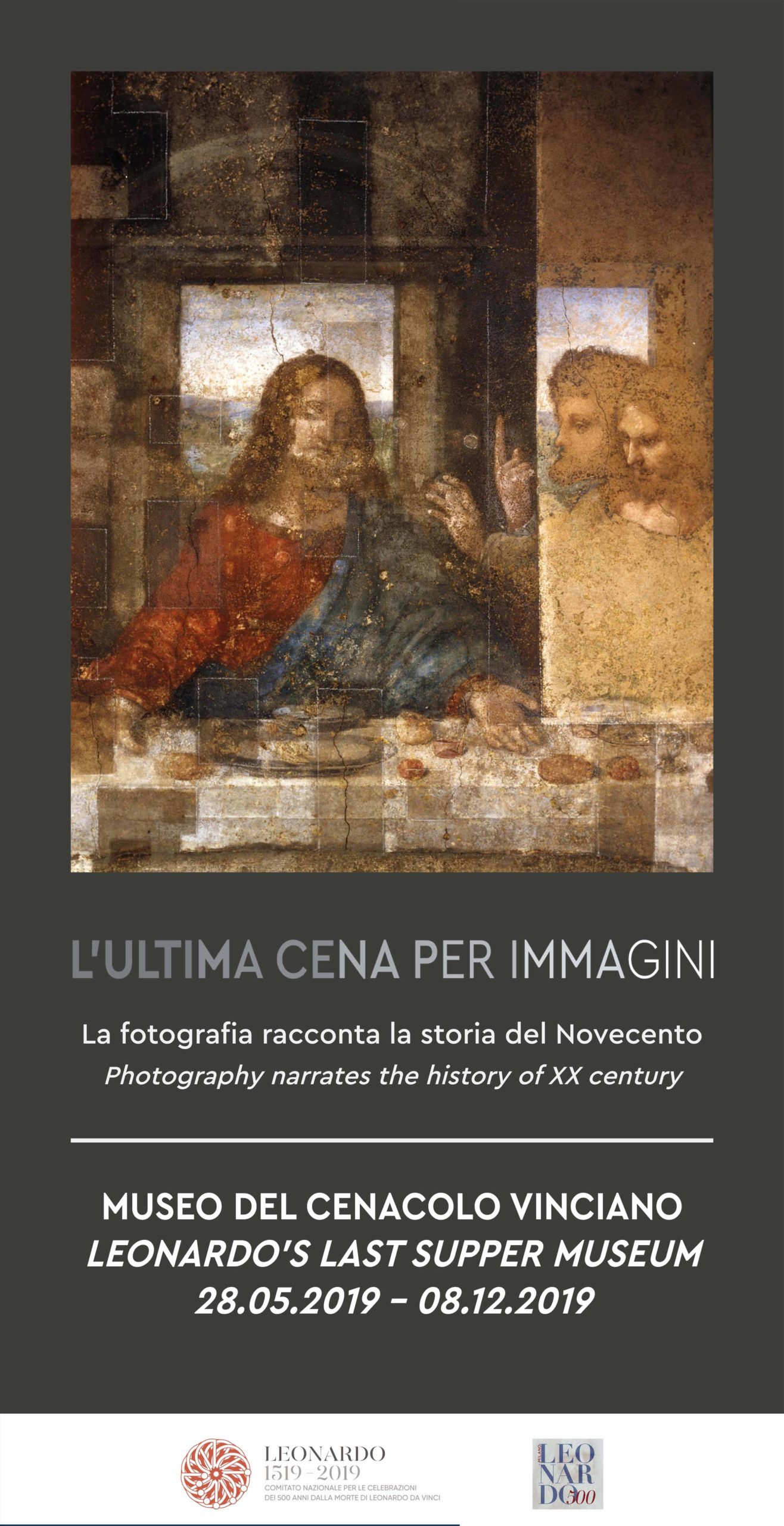

It is precisely in Milan that, in the former refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, is carefully kept one of Leonardo’s masterpiece: the Last Supper. For the occasion the Leonardo’s Last Supper Museum transformed its visit tour in order to walk the guests through its last century of life, through the exhibition “Ultima Cena per Immagini. Photography narrates the history of XX century”.

The poster of the exhibition, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

Between 1494 and 1498, commissioned by the Duke of Milan Ludovico il Morro, Leonardo painted a representation of the Last Supper in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo chose to capture the reactions of the disciples – “motion of the souls” – in the moment when Jesus announced that one them would have betrayed him.

Throughout the centuries the painting has endured invasions, famines and wars but the most descructive event was certainly the aerial bombings during the Second World War, luckily followed by important campaigns of restoration.

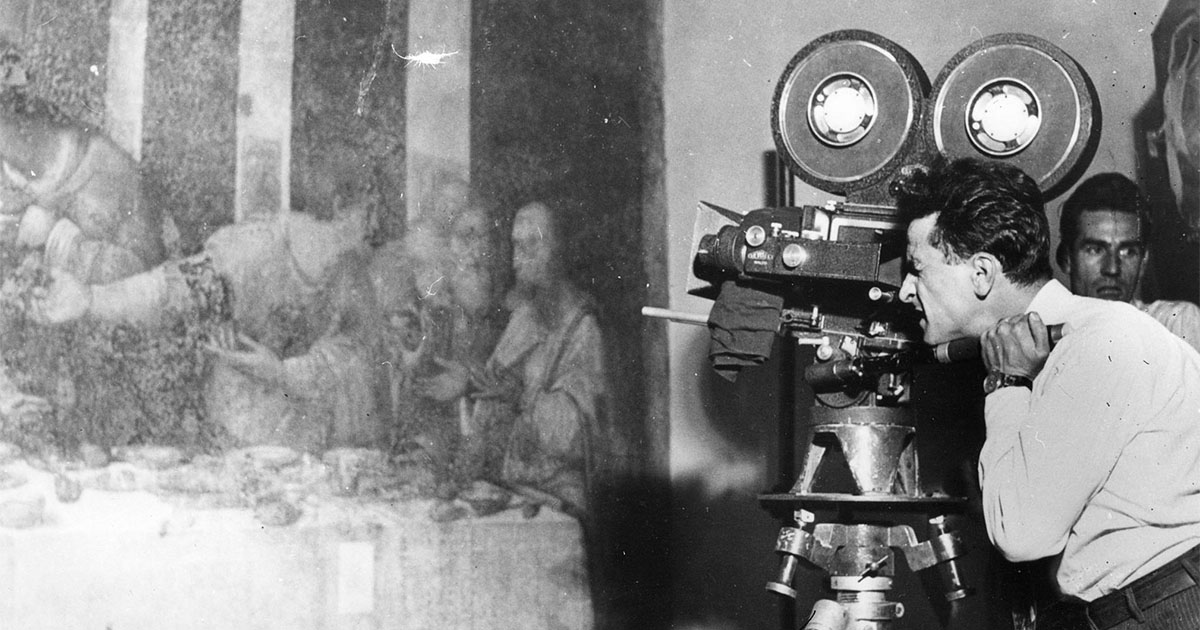

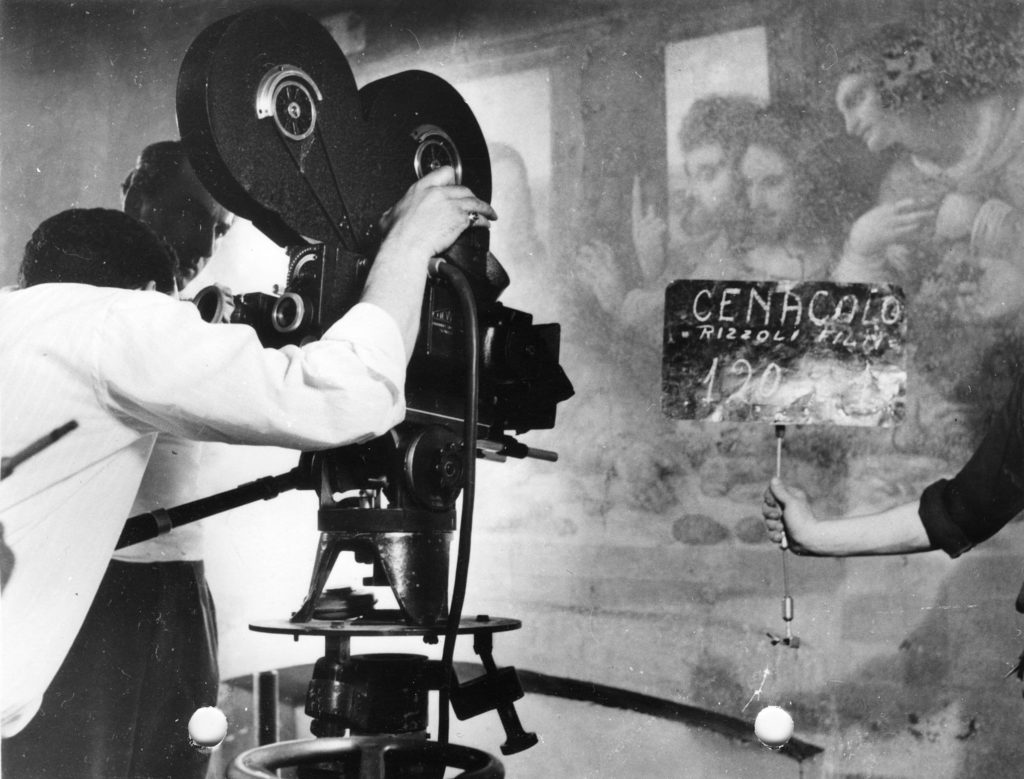

The Last Supper during the filming of “Il Miracolo della Cena. Le vicende del capolavoro di Leonardo da Vinci”; directed by Luigi Rognoni, 1953/Photo: Protographic Archive, former SBSAE of Milan/Pinacoteca di Brera, inv. no. 1080

The exhibition organized at the Leonardo’s Last Supper Museum has the precisely purpose to illustrate these events, through the reproduction of photographs and prints preserved in the historical archives of Milan Superintendences, an extraordinary and precious mine of information. In this context took place the last chapter of its digitization and cataloging, in order to create a complete digital catalog which can be consulted without compromising the delicate originals.

THE EXHIBITION

“Ultima Cena per Immagini” takes the visitors along the museum tour (1), telling the story of the spaces by using reproductions of those rare and precious historical pictures. The exhibition is ideally divided into three main topics: the complex of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the Museum, the bombings of the Second World War and the great restorations of the XX century.

The exhibition: the museum’s entrance, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: the Chiostro dei Morti with the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the picture after the bombing, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: the restarations’ hall, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: the wall with the pictures of refectory’s bombing, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: the touch screen in the restarations’ hall with a HQ picture of the Last Supper, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: the head of Filippo during the restorations of XX century, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: totems in the garden narrating the museum’s history, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: totems in the garden narrating the museum’s history, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

The exhibition: a digital version of the exhibition was installed at the MIC – Interactive Cinema Museum in Milan, 2019/Photo: Silvia Demetri

THE MUSEUM

The idea of opening the refectory to visitors dates back to the beginning of XIX century, housing new and old copies of the Last Supper in order to permit a deeper understanding of the painting, allowing to make comparisons and observations.

The building of a “museum of the Supper” was necessarily stopped by the advent of conflicts and it was only at the end of the world wars and reconstruction (1946-47) that visitors were finally able to go and see Leonardo’s Last Supper. An anomalous museum with only two art-works: the Last Supper on the north wall of the refectory and the Crucifixion of Donato da Montorfano, unluckily eclipsed by Leonardo, on the south wall.

The refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie set up with a sequence of copies and the painting of the Last Supper on the far wall, c.1895/Photo: Photographic Archive of the SABAP of Milan, inv. no.3406

THE BOMBING

During the Second World War Milan came under heavy fire from the British and American air forces and bombs hit the city several times, devastating buildings and monuments. Even the complex of Santa Maria delle Grazie did not remain unscathed, in the night between 15th and 16th August 1943 a bomb destroyed a side of the church, the Chiostro dei Morti – with the corridor leading to the entrance of the refectory – and above all the east wall of the refectory.

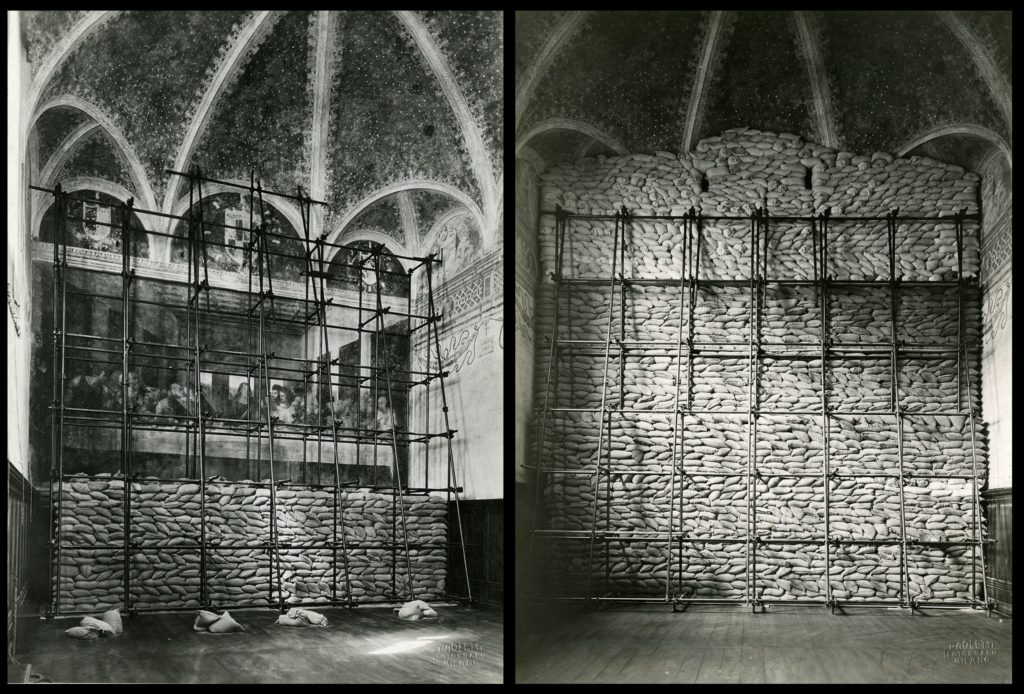

The painting of the Last Supper with its anti-aircraft protection of sandbags supported by metal scaffolding, 1940/Photo: Photographic Archive of the SABAP of Milan, inv. no. 766-769, photo by Paoletti

The Last Supper miracolously survived, protected by sandbags supported by a metal scaffolding and a temporary roof. However, following the prolonged exposure to atmospheric agents the state of conservation of the work was very precarious and it was necessary to wait until the end of the conflict to rebuild the damaged parts of convent and the museum, in 1946-1947.

“The cloister has quite literally gone […] the refectory is little more than a pile of rubble”

Gino Chierici, 1943

15th August 1943: bombing destroys the portico, the roof and the refectory wall, and heavily damages the church; the cloister is filled with rubble/Photo: Photographic Archive of the SABAP of Milan, inv. no.7

THE RESTORATIONS

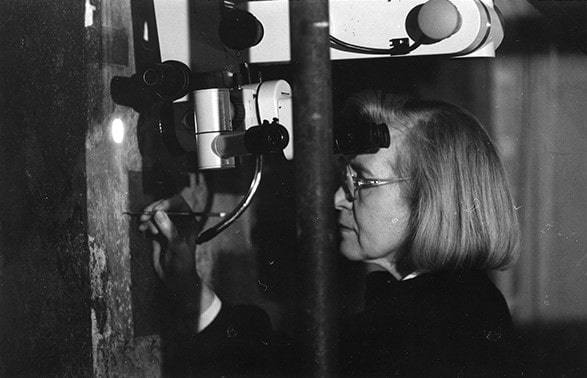

Detail during the restoration work by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, the cleaned patches show the contrast between the work’s state of conservation and its stage of restoration/Photo: Photographic laboratory Archive, former SBSAE of Milan/Pinacoteca di Brera, inv. no.1481

Over the centuries several attempts to halt the decay of this fragile painting have been carried out but it was only at the beginning of the XX century that restorers began to investigate Leonardo’s technique (2) and the causes of deterioration.

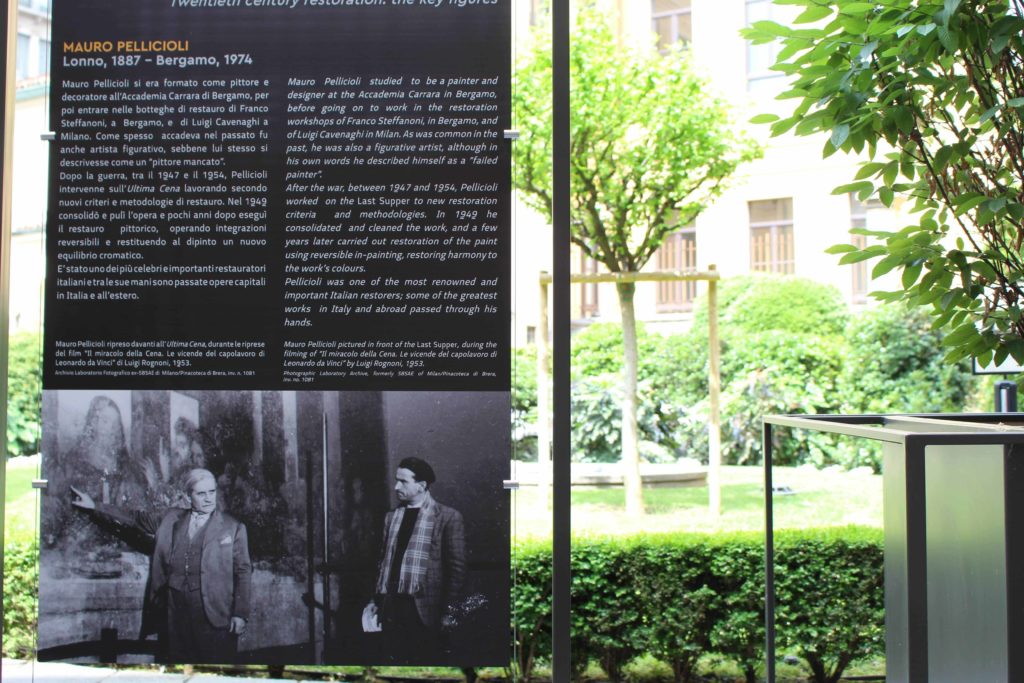

Mauro Pelliccioli between 1956 and 1954, after the rebuilding of the refectory, worked hard to consolidate the surface of the painting following a long exposure to elements, using wax-free shellac, without removing the older repainting. It has only been since 1977, with the twenty-year restoration by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, that it was marked an approach’s change: a restoration based on archeological approach and supported by scientific analyses. She consolidated the pigments of colour, removing older repainting and then carrying out a watercolour inpainting. It was the end of the restoration and the beginning of a new attention towards the preventive conservation of the Last Supper, through also the control of the temperature and humidity, air filtration system and quota entry for visitors.

“We were stuck by the paint’s strange appearance: rather than whitening, it appeared almost black […] swollen with damp, the surface of the Last Supper gave the impression of a spongy fabric”

Fernanda Wittgens, 1946

Restorer Pinin Brambilla Barcilon carrying restoration work on the Last Supper with the help of a microscope, 1982/Photo: Photographic laboratory Archive, formerly SBSAE of Milan/Pinacoteca di Brera, inv. no.1081

The project of Ultima Cena per Immagini was prompted by the desire to narrate a specific moment, that changed everything in the history of this piece of art. From the bombings to the restorations to get to see the Last Supper as it appears to us today. There could be no better way to do it than through the camera of those who were present in those moments, immortalizing them for us.

The Last Supper during the filming of “Il Miracolo della Cena. Le vicende del capolavoro di Leonardo da Vinci”; directed by Luigi Rognoni, 1953/Photo: Protographic Archive, former SBSAE of Milan/Pinacoteca di Brera, inv. no. 1083

(1) it is essential to remember that the museum tour, from the entrance to the refectory, is not just part of the exhibition spaces but has got also a conservative function. Thanks to a sophisticated plant system, visitors are “cleaned” along the way so as to guarantee control strict values (humidity and temperature) and air quality inside the refectory.

(2) in order to understand the complex situation of the Last Supper it is important to know something more about Leonardo’s painting techniques. He prefered a dry technique instead of fresco, consoldated also for its longer-lasting, because he felt the need to experiment and to continually work on previous layers to achieve the effect which made this painting at the same time unique and extremely fragile.