Karen Kiss anthropologist/archivist based in Budapest and Lindsay Taylor US-American anthropologist based in Berlin

The second article in our two-part series on exploring ways of reconsidering European heritage means and who’s historical narratives are included in it.

Read the first chapter exploring the debates around the dark heritage embodied by the recently toppled and attacked monuments here.

Iconoclasm is nothing new. Though to some it seems like a radical reaction, it’s actually a longstanding tradition that stretches back to ancient Rome, where defacement of statues was a way to express public disapproval. In response to extreme misdeeds, Romans would erase all traces of someone’s image and name, a practice called “damnatio memoriae.” To be excised from the collective memory of the city was a punishment worse than death in a city where public image and legacy were paramount. In the 16th century, Roman citizens would use an old statue’s base to post signs for venting their frustrations about politics and public life in general. These “talking statues” became a voice for the ordinary people of the city, almost like an early bulletin board.

Throughout the centuries, cases of “vandalism” continued whenever collective values needed readjustment. History is most often decided in the public eye. It’s natural for a society’s perspective to change, and the cultural landscape will reflect this. But the question remains on how to dispose of unwanted memorials.

When statues speak

As we explored in the first part of this article, an act of destruction can become a memorial of its own. Whether memorialized through photography, video, or another art form, a toppling statue serves as iconic imagery. No less powerful is an empty pedestal, which makes the removed object all the more conspicuous for its absence. One example of modern damnatio memoriae is the case of Benedict Arnold, a U.S. American general who defected to the British Army during the Revolutionary War. Arnold’s name or likeness has been excluded from several memorials to colonial troops, including a monument for the generals who served at the Battle of Saratoga. While somewhat ironically, the empty space has only ensured that people remember the figure represented by this absence, it also guaranteed that this name will forever be synonymous with treason and betrayal.

But removing a statue from its plinth doesn’t mean it should be destroyed forever. Statues still serve a purpose as historical artifacts. Much debate has surrounded the educational value of statues. Many who argue that statues should remain claim they have the power to teach about history, with those who want their removal dismissing this as a naive interpretation of how the public interacts with art. There are better ways to learn complex history than through a public monument, and the fact remains that a statue is an inherent glorification of its subject — simply adding an explanatory plaque does little to change this. But that doesn’t mean that these monuments lack historical value. To historians, statues can provide crucial evidence, not necessarily about the time-period of the person they represent, but about the time-period in which they were erected. If not destined for a long-term storage space, these statues should have a new life in a museum, where the context of their dark history can be fully appreciated by the public at leisure. In this way, statues can continue to “talk” to us, sharing with us not the idealization of an individual, but insight into the growing values of a society.

An example of this is the Memento Park in Budapest, which we already touched on in our previous article. The park was set up as a way to store the city’s Soviet statues, creating a space where the country’s difficult past is commemorated through the monuments, without them staying in Budapest’s public spaces. The park works almost like a massive ‘idolized’ soviet square, with the many monuments placed in symmetrical orientation with the flower bed shaped as a red star in the middle. The site embodies that importance of context. By playing all the monuments in the same space, their narratives are recontextualised from straight, official and unquestionable ‘storytellers’ to ‘fossils’ of history. This is further heightened by the small exhibition space opened outside the park, which outlines the history of the country’s communist dictatorship. On the other hand, the pieces themselves do not have any descriptions apart from the name of the square or street they originally stood. This allows visitors to imagine the original interaction with monuments, which lacked ‘context’ combined with the physical sensation of the tall, powerful monuments towering over the visitors.

New histories?

Iconoclasm and the recontextualisation of existing monuments and other heritage have been an important way of question dominant historical narratives. But what do we have to consider when creating our present ‘monuments’ and narratives? What can we do in the present to create and represent (European) heritage and institutions that include more diverse voices and that are able to cast a critical eye on the past?

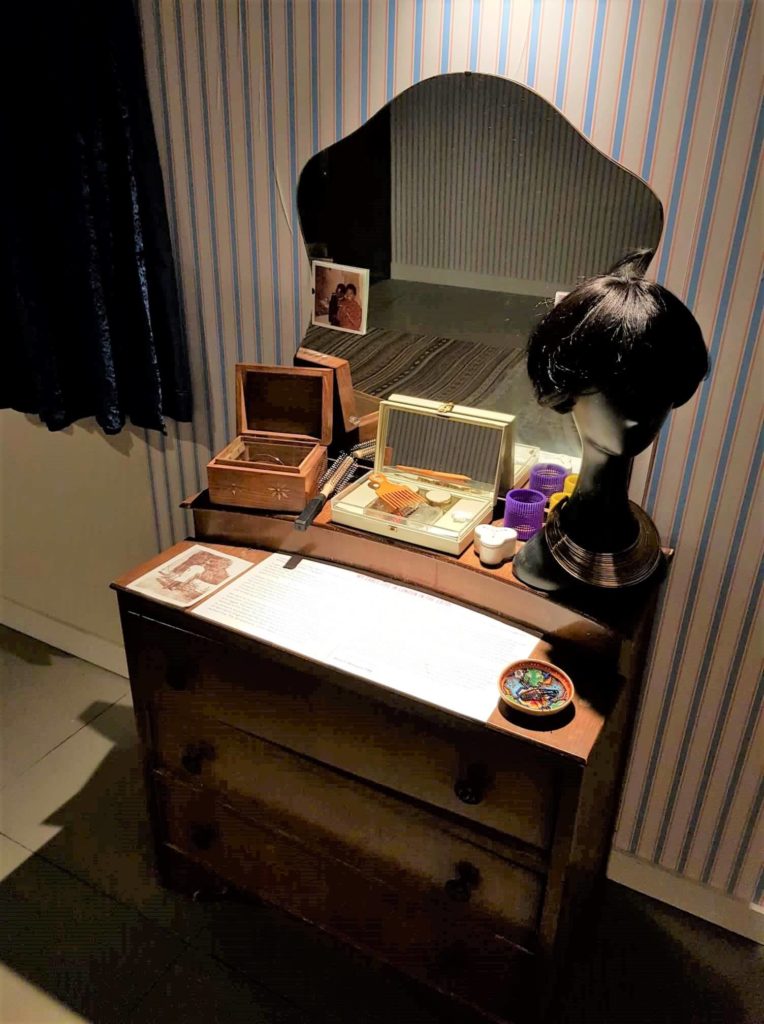

A good strategy could be to create institutions that focus on stories that are often excluded from a country’s traditional national identity and historical narratives. An example is the Migration Museum in London. Currently based in a shopping centre in south-east London the museum itself needs to travel as it does not have a permanent home. Their immersive exhibition a Room to Breathe features several rooms, like a bedroom and kitchen presenting everyday objects that were used by people arriving in the UK across the decades to create their new homes. Wandering through these intimate settings, the visitors can hear and read people’s stories and even recipes through which they can recreate the atmosphere of their home countries and heritage.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX