Warsaw, Poland

Even after a short period of time, distinct cultures within a single region can become mixed, the line between them blurred. After a millennium of shared history, they can become inextricable. Recorded Jewish history in Poland begins in the 11th century, and as the community developed and grew throughout the centuries, it became the center of Jewish culture. By World War II, Poland was home to the largest Jewish population in Europe. But the Holocaust suddenly and violently erased them from the cultural landscape. Within a few short years, 90% of Polish Jews were murdered, leaving Poland haunted by the question: how do you visualize the absence of three million lives?

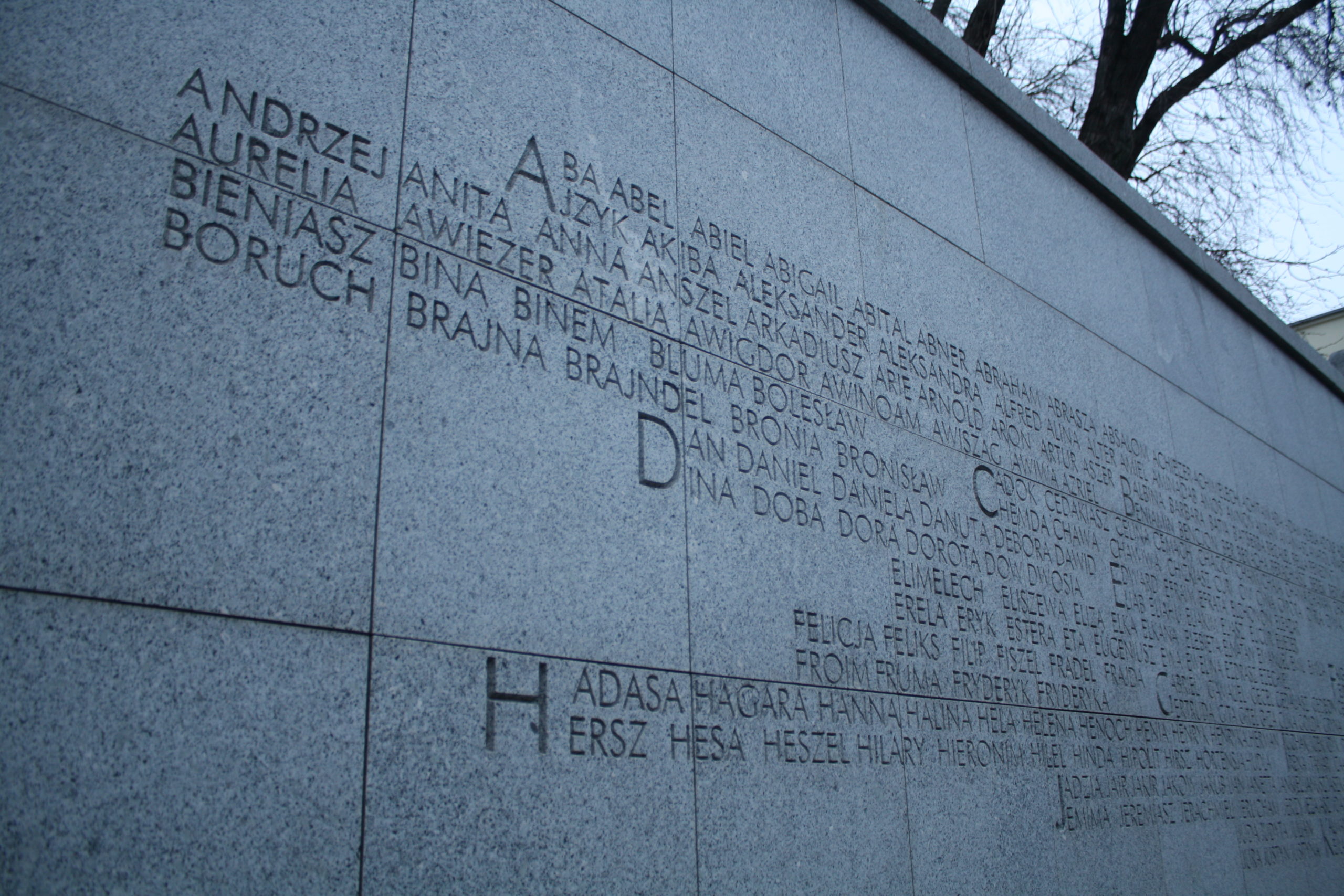

Warsaw’s first memorial to its murdered Jewish citizens was the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, built in 1948 to commemorate those who died in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest Jewish-ghetto in wartime Poland; it made up 2% of the city’s area and held around 30% of its citizens. Today, this residential area is dotted with memorials, most of which are relatively unassuming. Fragments of the Ghetto wall remain with informational plaques, a “Footbridge of Memory” marks the location of the infamous Ghetto bridge, and a commemorative stone can be found at Miła 18, where the bunker for the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) was located. But the crowning jewel of these memorials is the POLIN Museum. The largest and most visible site of Jewish remembrance in Warsaw, the museum documents not only the atrocities of the Holocaust, but the entirety of Judaism’s thousand-year history in Poland.

Inside Warsaw’s POLIN Museum

The museum is located directly in front of the memorial for the Ghetto Heroes, the two of them forming a somber duet. The museum remembers how Polish-Jews lived, the monument remembers how they died. Ambitious in scope, POLIN strives to convey the longevity and interconnectedness of Poland’s Jewish history – not just chronicling anti-semitism, but illustrating the cultural symbiosis between Poles and Jews.

The museum doesn’t rely on objects to tell this story, instead incorporating interactive elements to encourage active engagement rather than passive observation. This is a valuable approach from an educational perspective, but it also has a practical purpose. In the absence of tangible Jewish heritage, the museum is forced to adopt more creative means to educate its visitors.

Probably the most notable example is the museum’s of a wooden synagogue, an architectural style that developed around the 17th century in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Today, there are virtually no material traces of these synagogues left; they were nearly all destroyed during the war. Instead of relying solely on scant images or textual descriptions, POLIN commissioned a recreation from the Handshouse Studio in Massachusetts, USA. The studio, which specializes in traditional building methods, used the synagogue from Gwoździec as a model, since its architectural form and elaborately painted ceiling had been relatively well-documented at the time of its destruction. An international team of craftsmen, students, and volunteers of both Jewish and non-Jewish backgrounds rebuilt the cupola at an open-air museum in Sanok, Poland and later reconstructed it within the museum. The end result is a wonder to look at; viewers can admire the colorful overall effect and use digital monitors to enhance details and learn more about its iconography of the painted flora and fauna.

But the reconstruction’s value goes beyond what can be seen in POLIN today. Through the act of recreation, not only can the lost architectural aesthetic be recovered, but also the forgotten knowledge of the traditional artisanal handicraft. The wooden synagogues exemplify the scale of the loss sustained by the Jewish community and simultaneously provide a modern way to engage with Jewish culture through the act of recreation and reconstruction.

The politics of memory

As stunning as this museum is, one has to wonder who it’s for. Curator Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett acknowledged the public confusion at building a Jewish museum where so few Jews currently live, explaining that it’s essential to place the museum at the site of the atrocity, symbolically rising from the rubble. But there are some who view this decision more critically. Joseph Berger, a New York Times contributor of Jewish-Polish descent calls POLIN a “museum to atonement,” implying that it’s part of an attempt by the Polish government to use Jewish heritage for political and economical gain. It’s not a baseless claim – after all, in the museum’s direct surroundings are several accompanying monuments that focus not on the Jewish lives that were lost, but the attempts by Poles to save them. Perhaps the most revealing of these monuments is the Willy Brandt monument, which commemorates the infamous “Kniefall” by the West German Chancellor. Though that moment of penance was touching, does it deserve to be memorialized alongside the lives of those who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto? Its presence acts as a gentle reminder of who the perpetrators of the Holocaust really were, thus minimizing any wartime crimes on the Polish side. It’s understandable that Poland would like to distance themselves from the genocide committed on their land by foreign invaders, but there are many who believe this denies the acts of complicity between Poles and Nazis. Similarly, the country faced international criticism in 2018 after passing a law that censors accusations of Polish collaboration during the war, a sign that Poland is still struggling to face unsavory aspects of their own history.

It’s not only Poland’s international reputation and national pride that’s at stake. The vast diaspora of Polish-Jews represent a considerable market that Poland could attract with heritage tourism – assuming there’s something for them to visit. With tangible Jewish heritage effectively erased from the Polish landscape, there’s little to be found by those who return to rediscover their roots. Berger, who undertook such a journey himself, notes that none of the places his mother recalled could still be found on a map; the Jewish communities of his parents lived on only in the memories of their oldest neighbors. Yet the Jewish heritage market is thriving, and the tourists need to be directed somewhere. By default, POLIN Museum becomes a destination for those who can no longer retrace their personal roots to discover the history of their community.

Small in number, great in cultural presence

Poland can never wholly recover the tangible heritage that was lost during the Holocaust, no matter how many monuments they build to commemorate it. But this is not to say that the thousand years of cultural symbiosis between Poles and Jews is at an end. Instead, it’s resurfacing in brand new ways. Though the practices that exemplified Jewish culture in the past have all but disappeared, new ways of engaging Jewishness have manifested – such as the interfaith collaboration to reconstruct a historic wooden synagogue. And as many rediscover their lost Jewish heritage, Poland has become home to a steadily growing Jewish community. As Kirschenblatt-Gimblett aptly noted, POLIN has become not a museum that chronicles history, but one that creates it. While it traces a thousand years of history, it ultimately represents an invitation for the next thousand years of Polish-Jewish cultural interconnection.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX