By Samuel Oer de Almeida,

a Classical archaeologist from Germany

In the southwest of Stuttgart, the capital city of the federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg in southern Germany, a rich architectural and sculptural heritage exhibited in the decelerating atmosphere of a Renaissance style garden is to be discovered.

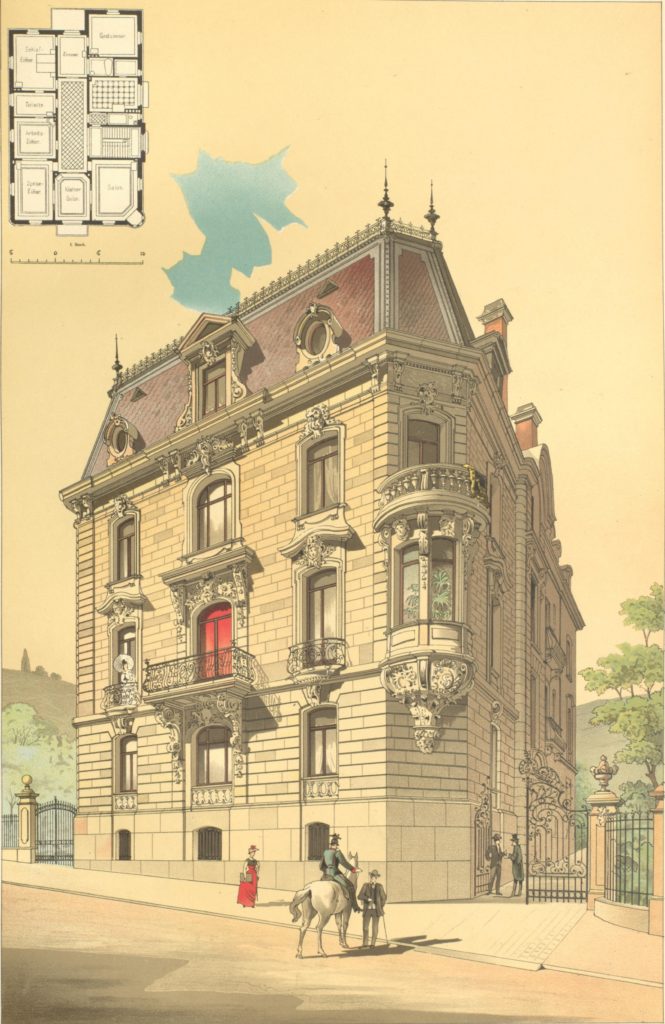

Karl von Ostertag-Siegle (1860–1924), the son-in-law of the wealthy Stuttgart entrepreneur Gustav Siegle (1840–1905), who had founded a prosperous paint factory in the 19th century, owned an urban villa at Mörikestrasse 24. The representative residence was built on the initiative of his father-in-law in the 1880s and lines together with several other lavish 19th century villas the street, forming one of the most distinguished living areas of the city.

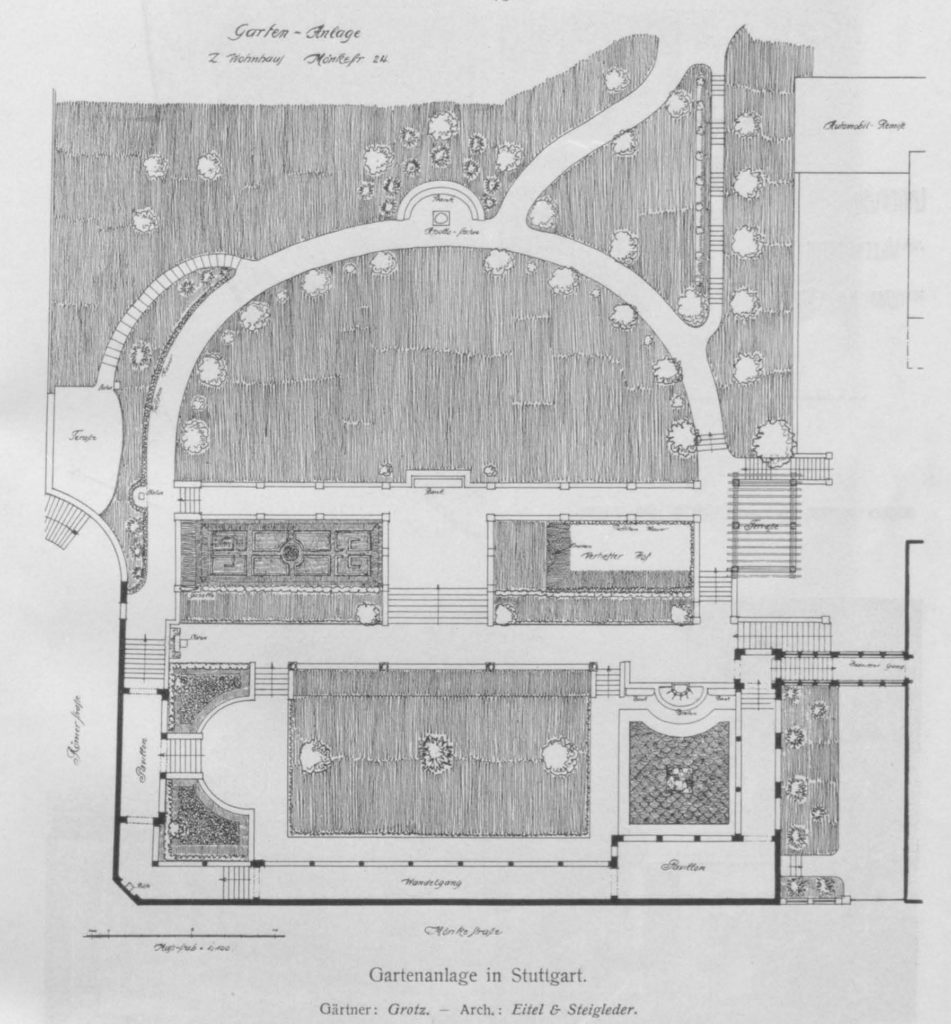

In 1905, Ostertag-Siegle commissioned the architects Albrecht Eitel (1866–1934) and Eugen Steigleder (1876–1941) to design a garden complex adjacent to his villa, making use of the space immediately southwest of the building which initially laid waste. The architects adapted a historicist design inspired by Italian Renaissance gardens of the 17th and 18th centuries, which were characterised by green areas, terraces, and water features. The published groundplan of the early 20th century shows the complex’s general layout. The park is embedded in the natural geography of the area. It is situated on the terraced southeastern slopes of an urban hill named Karlshöhe, which is covered with small vineyards. The garden largely follows a symmetrical layout. At its back, a semi-circular exedra forms the highest point and visual centre of the complex. Starting at the exedra, bent paths close in a semi-circular green area and lead downwards to a crossing way which centrally opens onto a lower path. In the west, a small terrace offers a great view over the complex. The lowest part adjacent to the bordering street in the southeast is dominated by a large portico closing in a central green area. On the west side, a stairway framed by green elements leads to a rectangular pavilion, while on the east side, a southeastwardly oriented semi-circular fountain framed by two benches lies in front of a paved court leading to another pavilion. The latter should originally have been connected via a portico to a short bridge leading to the villa, which was probably demolished or has never been executed. Instead, two entrances with staircases were built at the garden’s northeast side framing a raised terrace.

Karl von Ostertag-Siegle was a passionate collector of antiquities. On at least two journeys to Italy—which still was a fashionable thing to do for a man with his social standing—, he acquired truckloads of fragments of Roman sculpture and architecture from Rome. All purchased objects sadly lack further information on their origin—trade in antiquities was not yet legally controlled, as it is today. Nearly 200 marble fragments were successively attached to the southeastern portico’s back wall, resembling the visual appearance of Italian cloisters wallpapered with antiquities. The collection was not just an intriguing eyecatcher but also a witness to the owner’s classical education and, thus, his cultural capital. The objects are currently being studied by Thomas Schäfer and his colleagues, as well as students, including me, from the Institute of Classical Archaeology at the University of Tübingen—eventually, the project will culminate in the scientific publication of the collection. The shown objects shall give an impression of the broad spectrum of purchased antiquities: a head fragment of a colossal statue of the Roman Emperor Trajan (53–117 CE), a well-preserved fragment of a Roman coffered ceiling, and a Latin funeral inscription marking the burial of a certain Helico.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

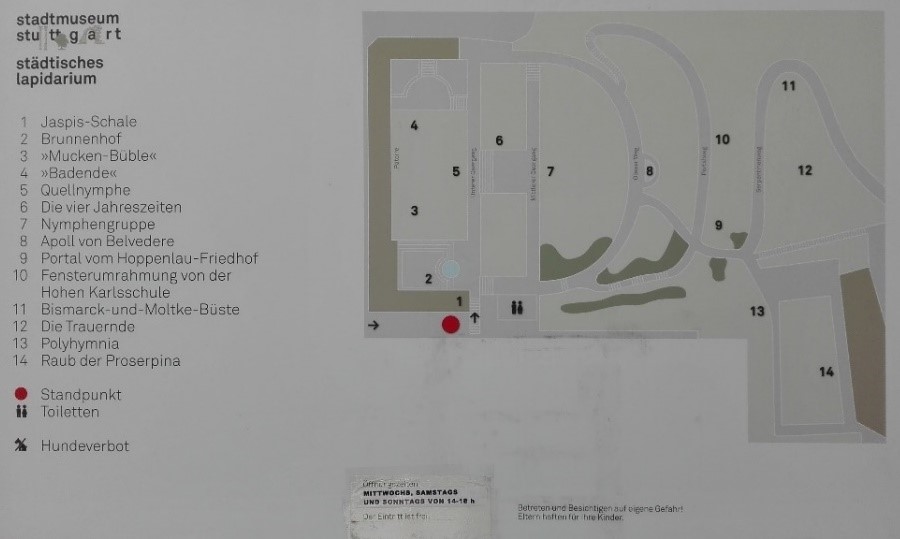

In 1935, the villa passed over into the city’s property. A few years later, in 1950, the heirs finally decided to sell the garden as well. The park received additional space in its north two years later, forming an upper part, which is structured by a steep meandering path and features another portico in its east.

In the course of the reshaping of Stuttgart’s city centre around the year 1900, many public and private buildings were broken up. During this process, individual architectural elements of the demolished buildings have been stored in the cloister of a former urban Dominican monastery. Thus, the architectural and cultural heritage of Stuttgart’s historic city centre was conflated in a relatively small space which was consequentially transformed into a public museum. During the Second World War, this old Lapidarium (lapis [Latin] = stone) was eventually destroyed by bombardments in September 1944. Only three months after the end of the war in early May 1945, the Municipal Commission for the Preservation of Works of Art and Architectural Monuments (Städtische Kommission zur Erhaltung von Kunstwerken und Baudenkmalen) was founded in agreement with the American occupation force. The commission, under the guidance of the historian Gustav Weis and the building official Wilhelm Speidel, developed a remarkable activity in retrieving and preserving large numbers of architectural fragments, sculptures, as well as inscriptions from the war-ravaged city centre—also from the old Lapidarium. The aim was to collect and appealingly present the city’s architectural and cultural history to the public.

Now in public hand, the garden complex in southwestern Stuttgart was initially used as a provisional shelter for the rescued stony heritage of the city. In lack of a reasonable alternative, the garden was eventually transformed into the new urban Lapidarium of Stuttgart inaugurated on the 8th of July 1950 by the city’s mayor Arnulf Klett (1905–1974). During the opening ceremony, Weis described its development with the following words:

Thus, out of a complex with a superb garden, initially thought as a makeshift shelter, a downright ideal urban open-air museum arose…

(So entstand aus einer als Notunterkunft gedachten Anlage in Verbindung mit dem herrlichen Garten ein geradezu ideales Freilichtmuseum der Stadt…)

The commission and the city pursued a pragmatic solution by using the former private garden complex as a public space for leisure, art, and cultural education. After Weis’s death in 1961, the Lapidarium fell into oblivion—even many long-established inhabitants of Stuttgart do not know about its existence until the present day. However, in 1999, the complex received cultural monument status improving its visibility. Today, augmented by donations and purchases, the Lapidarium contains over 200 modern objects covering over five centuries of Stuttgart’s urban history and nearly 200 antiquities from the ancient city of Rome.

The garden complex of the early 20th century had already featured sculptural décor, which formed an essential part of the park’s original concept. The landscape was structured by architectural elements, while the built environment was populated by classicising artworks. In the central exedra, Ludwig von Hofer’s (1801–1887) modern copy of the famous Apollo Belvedere overlooked the complex. The erection of the statue around 1908 continued a general trend of the 19th century. Since it has been venerated as one of the most beautiful ancient sculptures by leading art historians and early archaeologists of the previous century, Apollo Belvedere became part of the sculptural canon everyone with a claim to classical education had to possess and display in his house or garden. In this light, the dominant position of the statue in the Stuttgart Lapidarium does not surprise—it verbatim topped all other works of art.

Not only the exedra but also the park’s lower parts were adorned with classicising art. Both pavilions exhibit figural supporting pillars depicting the horned god of shepherds Pan playing his pipes and a female companion sounding a double flute.

The court in front of the eastern pavilion is paved with a mosaic centrally showing the mythical ancient Greek singer Orpheus who sits on a rock and plays his lyre surrounded by an idyllic natural landscape and listening animals. The Lapidarium’s mosaic is a modern copy of a Roman original found in Rottweil south of Stuttgart.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

The fountain north of the court exhibits a marble relief sculptured by Emil Julius Epple (1877–1948) and shows a scooping female framed by two water birds. Evidently, the park’s original concept had an overall classicising colouration.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

The oldest monument of the post-war collection is the portal of one of Stuttgart’s oldest houses, the so-called Alte Steinhaus, from around 1250—the façade’s portal was secondarily pieced together with other fragments of the house.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

Several fragments of the Neue Lusthaus (1584–1593), a Mannerist building designed to host aristocratic celebrations and erected by the architect Georg Beer (1527–1600). The building had already been converted multiple times, as a fire in early 1902 destroyed most of the structure, which consequently was nearly fully demolished.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

The portal of the house of the famous Renaissance architect Heinrich Schickhardt (1558–1635) is another interesting piece of Stuttgart’s architectural heritage. It shows a mask in its upper left corner and an inscription plaque of the city commemorating the 300th death-day of Schickhardt in 1935.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the centre of the upper crossing path, a zinc cast of an unknown artist reproduces a statue of Johann Heinrich von Dannecker (1758–1841) depicting the nymphs of water and meadows.

Architectural elements of the Kronprinzenpalais, an urban palace built under King William I of Württemberg (1781–1864) in 1846–1850 by the architect Ludwig Friedrich von Gaab (1800–1869), are also exhibited in the Lapidarium. The large building in the historic city centre was designed in Roman Renaissance style and mainly served—with interruptions—as the urban residence of the crown princes of Württemberg. After the First World War, the palace was used for exhibitions—eventually, the National Socialists organised a highly ideological display of the allegedly subversive art of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement and an exhibition glorifying war. In 1963, following a long and passionate debate, the building was finally demolished in the course of urbanistic measures.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

One of the historical as well as material highlights of the collection is a monumental jasper bowl of Olga Nikolaevna (1822–1892), the daughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia (1796–1855) and Queen of Württemberg. It was her father who gifted the basin to her in 1853.

(© Gerd Leibrock / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Moreover, reliefs and sculptures of Bertel von Thorvaldsen (1770–1844), Josef Zeitler (1871–1958), and various other artists are displayed. Statues, such as the caryatides or the Orpheus, harmonise well with the originally classicising theme of the complex, although in case of the latter following a different style.

The garden’s extraordinary composition encompassing Roman fragments, medieval and Renaissance architecture, as well as 19th century statuary and reliefs makes the urban Lapidarium of Stuttgart a heritage melting pot. Different temporal as well as spatial spheres overlap in a relatively small space, creating an intriguing place of cultural heritage which awaits to be visited, explored, and appreciated.

The Lapidarium opens its doors for the public in the warm season of the year—between June and September. In its distinctive atmosphere, readings, theatre performances, as well as concerts take place annually.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX