On the road to Resilience through Cultural Heritage and Industry

by Jacopo Ibello and Marita Oikonomidou

Coming from two countries in the south of Europe, we were intrigued as soon as we heard about Apolda, a small German town that, despite its great industrial history, is nowadays faced with the effects of economic crisis. It was inevitable – we had to visit it and see it for ourselves: Would we face the dreadful sight of old abandoned buildings and empty streets? Were we about to embark on an adventure in a ghost town? Unfortunately, we were already familiar with similar cases of decaying towns with once blooming economies. After all, the revitalisation of (post)industrial cities and towns is one of the toughest challenges for Europe. Especially for places like Apolda where the usual process of de-industrialisation met with the fall of a socialist state and the difficulty to survive in the global market.

Before we continue with our adventure, let’s take a glimpse into Apolda’s past and present. This old, small town in the green heart of Thuringia has for centuries been the centre of high-skilled manufacturing: bells, books, knitwear but also clocks and, for a few years, even cars. Here, industry has not only been an economic resource, but it has made up a part of the community’s culture and identity. The consequence of losing it has meant a greater sense of loss: the loss of jobs, of hope for future and, of course, a loss of people. Thousands of people: the number of inhabitants has dropped from 37,000 in 1947 to only 22,000 today.

INDUSTRY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE

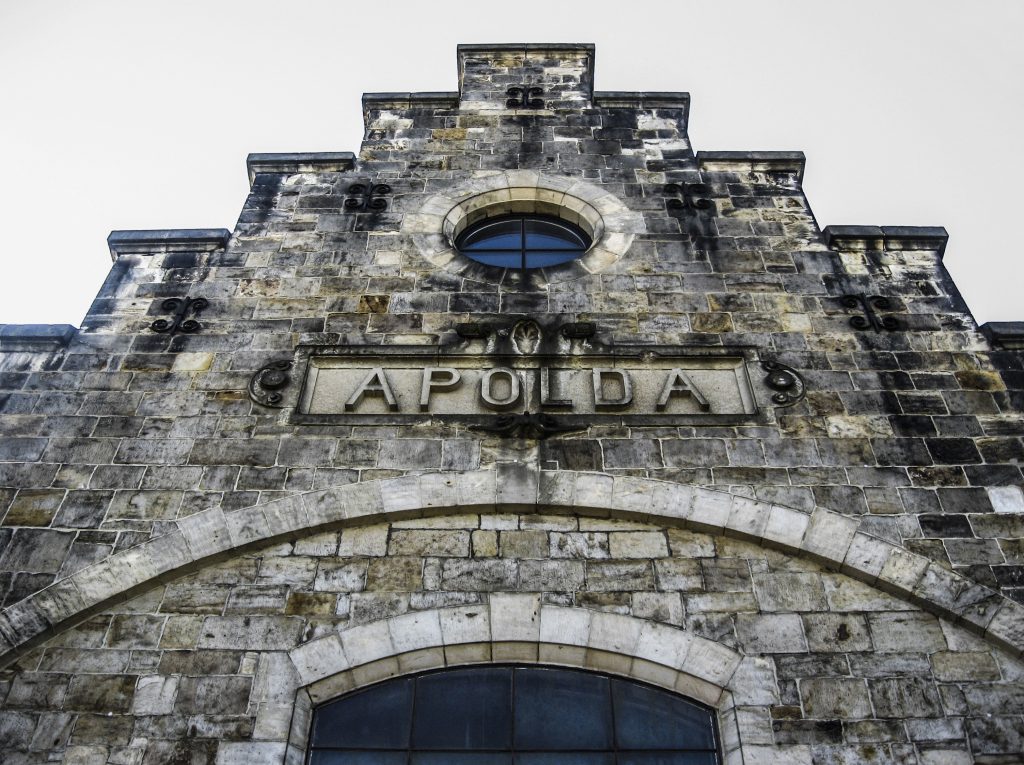

With the aboven mind, we set out to explore the connection between industry and culture in the context of today’s challenges. It is a connection that many still do not see, understand or even accept, but here it was so evident. To witness it, we needed only to walk down the street that brought us from the beautiful, neo-Renaissance train station to the historic town centre where a long series of gorgeous architecture unfolded in front of us, with factories and entrepreneurs’ villas alternating each other. This is a rare feature: industrialists usually built their houses far away from noisy and dirty industrial areas and striking workers. But here, villas and factories were lined up together on the town “Boulevard” (Bahnhofstraße), as they wanted visitors arriving from the station to know who and what really mattered in town.

Today, the conditions of these old industrial buildings vary. Some of them are abandoned whereas others have been reused. All of them, however, represent what matters now in Apolda:

Besides being testimony to the collective memory of the past as one expects monuments to be, they show the transitional period of the town – a transition in which they too should play a role.

In doing this, the Bahnhofstraße could be one of the axes of cultural tourism development, like an “Industrial Culture Trail”, and could perhaps even be integrated with other regional and national itineraries. Apolda could gain new life through the revitalisation of the Bahnhofstraße, a process that already seems to be happening, albeit mostly in the section closer to the centre.

THE PAST IN THE PRESENT

Walking down the Bahnhofstraße, we could sense the strong presence of the past. On several occasions, we felt like we had just travelled with a time machine back to the era of the Industrial Revolution. We could easily imagine the stylish bourgeoisie out on the streets and the typical beating noise of the looms in the background. The many empty shops only add to the sense of time being frozen with their old signs although, unfortunately, this is rather due to the current financial crisis than to a preservation plan for the urban landscape. The reconstruction and preservation of the Persil Clock in front of the abandoned ROTA factory by a local association nevertheless indicates that the community cares about its heritage.

It was this indication of care for the preservation of heritage that we noticed as soon as we stepped onto the Bahnhofstraße and that inspired us to actively go out in search of the local industrial culture. We were in awe of the imposing yet lifeless industrial buildings, but needed to push forward and explore the places where new life has been breathed into these heritage monuments. So, where better to start than from the GlockenStadtMuseum Apolda, or simply put, the Bell Museum?

The building itself, which used to be an entrepreneur’s villa, dates back from the mid-1800s and now exhibits Apolda’s local history tracing the evolution of the bell and textile industries over past centuries. Between the 18th and 20th centuries, church towers all over Germany were equipped with bells from Apolda’s foundries. Not much remain of this tradition, apart from the comprehensive exhibition in the museum. However, if you don’t mind climbing a bit, you can go on the top of the Lutherkirche (Luther’s Church) and admire – along with a spectacular view over the town – a group of original Apolda bells.

Among the numerous villas in the town, the Kunsthaus Apolda Avantgarde, an exhibition hall dedicated to contemporary art that’s importance goes beyond regional borders, is also worthy of a visit. This building is one of the best examples showing how the connection between industry and culture has already started taking hold in Apolda.

Another equally pleasant surprise: some artists took the meaning of Industriekultur (the particular German word identifying “industrial heritage”), very seriously. They used one of the abandoned textile factories to bring to life the Kulturfabrik – an inspiring place with ateliers for visiting artists and spaces for temporary exhibitions.

Continuing our walk down the Bahnhofstraße, we couldn’t possibly miss the Zimmermann factory,a massive brick building dating back to 1882. This huge complex hosted a major textile company in Apolda and today, after a restoration that mixed together old and new architecture, it is the seat of the regional council administration (Landratsamt). Even though the interior has lost the traces of the past, the series of beautiful terracotta friezes on the Bahnhofstraße side displays scenes of the textile industry, with puttoes shearing sheep or working at looms.

By this time, Apolda’s industrial history had so intrigued us that we ended up visiting all the old factories we could find – no easy feat! –, using the map and photos of the visited factories at the end of the article, so can you! We strayed from the Bahnhofstraße and passed under the railway viaduct, a stone giant built in 1846.

Our destination was the Eiermann Building (Eiermannbau), named in honour of its architect, Egon Eiermann, who designed it in 1938 and would later become famous for the Kaiser Wilhelm Church in Berlin. It used to host a fire-extinguisher factory but today, despite restoration and some efforts of reuse, it remains empty.

Even though there are many deserted industrial buildings in Apolda, we know that industry, is still alive and does not belonging only to the past. For this reason, we were very interested in visiting the Vereinsbrauerei Apolda, the local brewery founded in 1887 that produces beer to this day. The plant, which consists of several historic buildings, can be visited during the many events organised inside it. Although we arrived completely unexpectedly, the staff was very welcoming and kind enough to briefly guide us through the brewery and allowed us to take some photos.

AN ACE UP APOLDA’S SLEEVE

Apolda undoubtedly has much to offer, and not only to industrial heritage lovers. It is a place worth-visiting for its authenticity mixed with the melancholic taste of bygone splendour. It takes you on a journey through the past, yet leaves you with the sense of unfulfilled potential. This is because, despite current adversities, Apolda can become even more exciting – if only it realises that there are some hidden cards up its sleeve; of which its industrial heritage might yet be an ace. Thus we left this quiet yet revealing town in green Thuringia with an answer to a question concerning all European countries: