Discovering the architectural and industrial heritage of an Italian mining town

Machine town, mining town, company town

This is how Carbonia still describes itself to underline that its destiny has always been managed by outside forces rather than its own citizens. It was one of the new towns founded during the Italian Fascist regime (1922-1945), created by the State in an attempt to populate unhealthier and more desolate areas of Italy, forcing people from other poor areas into mass displacement. These towns were designed by Mussolini’s star architects with the purpose to reflect Fascist ideology in everyday life.

The coat of arms of Carbonia, showing a miner’s lamp over the coal.

Carbonia, located in southwestern Sardinia, isn’t merely one of the 1930s new towns, but it is also a company town: a place where power doesn’t refer to a mayor and a town council, but to the company owning the factory (which is also the main source of livelihood for the inhabitants). This company does not only own the production plant, but also the streets, the houses, the public services and buildings. It even owns the town hall.

The town hall of Carbonia.

This is a place where “public” has a curious meaning and, reversely, private property sometimes doesn’t exist. A house, for example is seen only as an accommodation, not as an investment made to the benefit of your future and your family. No longer a safe refuge, the house becomes a form of blackmail used to control workers: if someone rebels against the company, he can easily be replaced and his house given to a new, more compliant worker.

The “Autarkic Commune”

With regards to company towns, Carbonia has something that makes it, tragically, unique: the business on which it was founded was doomed from the start. The coal of Sulcis (the region where Carbonia lies) was discovered in the XIX century, but it was immediately considered unsuitable as an energy resource as its sulphur content is too high. This is the reason why coal mining has never taken off here, except during the Fascist autarky, and Italy still prefers to import it.

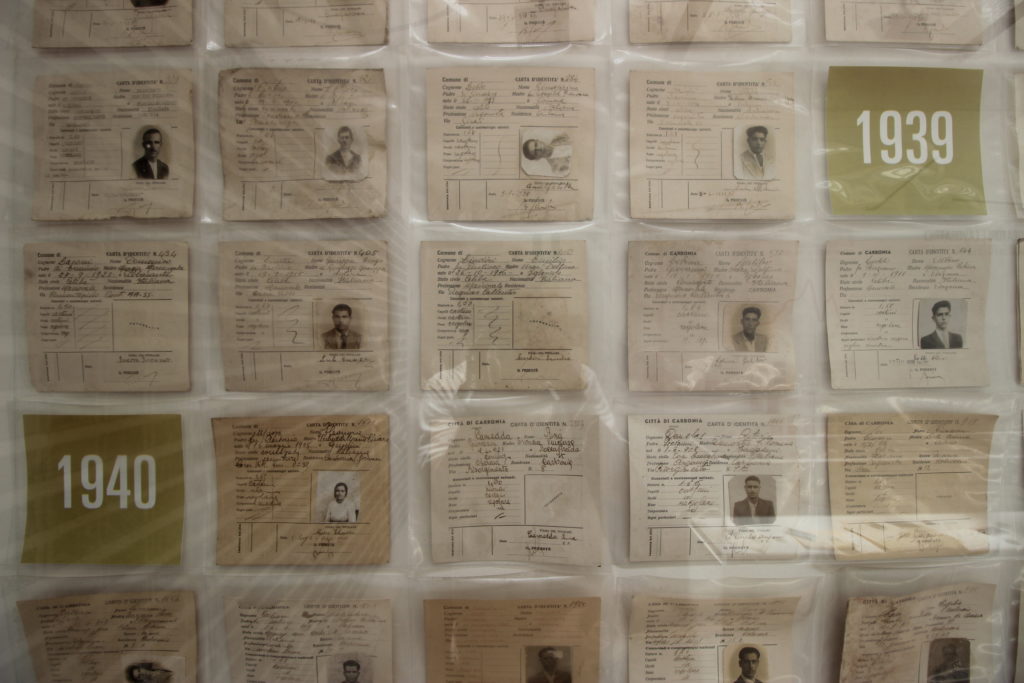

Nevertheless, during the 1930s, the regime initiated mass-scale industrialisation and urbanisation of the Sulcis region. The sanctions ordered by the League of Nations after the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936 complicated the supply of raw materials. In response to this, the government launched a programme of national autarky: a process during which a country aims to become self-sufficient, even supplying its own coal for power and steel production. Thus, men and women from Sardinia and other parts of Italy populated what was called “a malarial and desert land”. Farmers moved there for a different type of cultivation: the extraction of coal (200-300 metres underground), a product of the land that didn’t feed the workers, but that was rather used to “forge the weapons of war and peace”.

Mining town, Garden town

Cesare Valle and other architects were called to design Carbonia, the Autarkic Commune, the machine company town. They shaped a place where centre, main square, church and town hall were additions to the factory, the Great Mine of Serbariu.

This was the real centre, the final destination of streets and lives. All around, groups of workers’ houses were neatly aligned: the first ones were built in a rural style, close to the bucolic, “garden town” ideal that Fascism wanted to spread. But after its foundation in 1938, thousands and thousands of people moved to Carbonia and the houses were designed in a more practical “social housing” style. The garden town promise wasn’t kept.

The end… or not?

Inhabitants reached 60 000 during the Second World War. When the war ended, and autarky with it, Carbonia also had to come to an end. Oil and the ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community) made Sulcis coal an even less economically viable option. While Italy flourished during the 1950s-60s post-war boom, Carbonia in the same period lost half of its population and risked disappearance. People who came here as emigrants were forced to migrate abroad, some of them going to work in other coal mines.

The town is still there despite its being plagued by the same problems that it has endured for 50 years. Carbonia is probably not destined to become derelict, but, like many other towns, it is a place with old stories to tell and new ones still to be invented.

The first of these stories concerns its urban shape: once taken out of their political context, Fascist buildings and town planning of the 1930s, the planning of the 1930s undoubtedly shows attention being paid to peoples’ needs; something Italy missed during the post-war reconstruction. There is a noticeable attempt to relieve the harshness of the mining work through urban planning. The social housing buildings, even if far from the rural design of the first houses, were equipped with advanced services and equipment for the time.

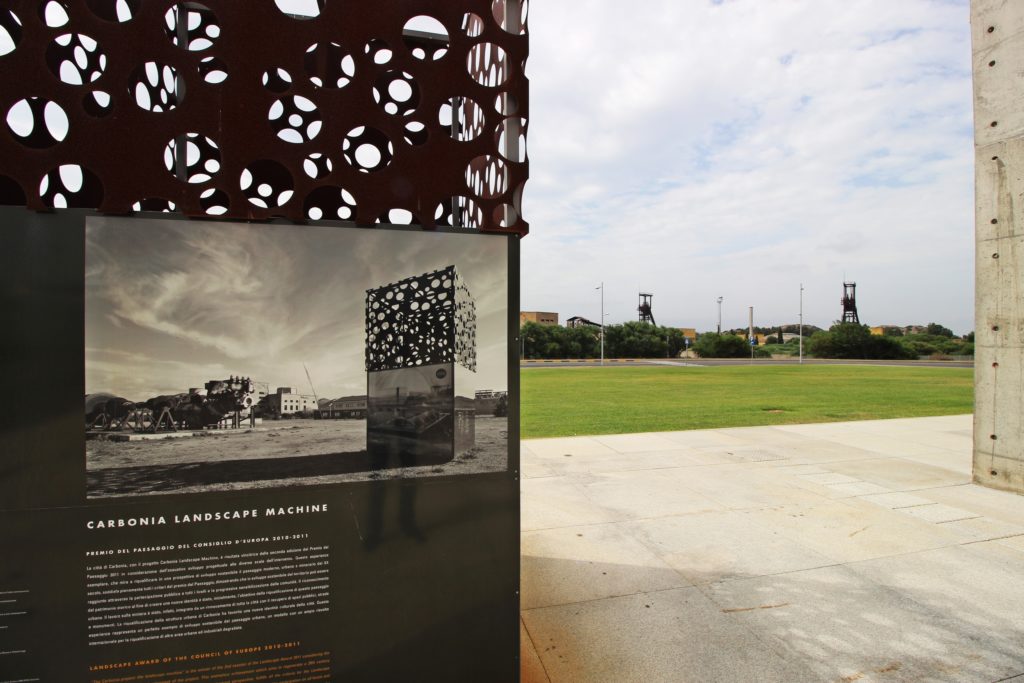

The open-air museum…

This modern avant-garde is told by CIAM (Carbonia Itinerari di Architettura Moderna or Modern Architectural Itineraries in Carbonia), a route to discover Carbonia’s architecture and planning. It includes beautifully designed totems, located at sightseeing points, that explain the history, projects, architects and neighbourhoods of the town. This is a true example of the cultural enhancement of modern heritage, which is still rare in Italy due to the country’s difficult relationship with its Fascist legacy.

… and the underground museum

Carbonia however can’t leave aside the Great Mine of Serbariu, since it gave birth to the town. Even today, upon arrival, you are met first by the mine and then the town. Coal hasn’t been extracted here for 50 years, and it is time to reverse the situation: the mine must now become a different resource for Carbonia. After decades of abandon, the beautiful industrial complex was restored in 2009 and is now a park with a museum, a visitable mining tunnel, a research centre and a restaurant.

After 70 years, the Great Mine of Serbariu remains the true centre of Carbonia, and is one of the most successful cases of industrial tourism in Italy. But many people go there only to visit the fake (even if beautifully replicated) mining gallery, completely avoiding the town. The latter is an open-air museum of modern architecture: walking along its streets and squares, you understand how the mine forged the shape of the town. Some company buildings, like the workers’ club and the director’s villa, host events and cultural exhibitions.

The “youngest Italian Commune” (as it was called by the Fascists after its foundation) already has a great history behind it, told underground in the mine and in the workers’ houses. Today, the Machine Town is also fed by culture, something its founders surely wouldn’t have wanted.